Jess Curtis / Gravity • Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

(Preview excerpt)

Jess Curtis / Gravity

February 28, 2010

Presented at CounterPULSE (San Francisco) as part of Gravity’s Intercontinental Collaborations 4.

Created & performed by Maria Francesca Scaroni, Jörg Müller, Claire Cunningham, David Toole, Jess Curtis and dramaturg/provocateur Guillermo Gomez Peña. Conceived and directed by Jess Curtis.

The stage is filled with the remnants of past performances, stuff that seems to have lost either its meaning or function. Objects from theater prop rooms: mannequin parts, black cubes, an old fridge, a child’s desk, a vintage gurney, a bike, a mirror, and even the kitchen sink, ba da ba. This is the trash of representation, stuff that looks like or evokes or locates… The appearance of the sink suggests a hint of vaudeville, that US American entertainment fusion of dance, comedy, circus, sideshow, and cultural performance.

Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

includes all of these elements, but under the influence of contemporary dance and performance these elements are either reduced to abstract essence or maximized into camp excess. The mashup of these tendencies - towards essence or excess - defines the field of play for this team of improvisers.

By referring to the bodies as Non/Fictional, Curtis emphasizes the impossibility of denying the fiction within nonfiction, the imaginary within the real. The slash that interrupts the more commonly used ‘nonfiction’ intervenes on a simple reading of nonfictional as non-imaginary, not-pretend. The bodies in this carefully constructed mess recycle and repurpose objects as easily as personae, changing costumes and attitudes, wigs and positions. In Dances for… the body is real is a theatrical construction is a performance is an unstable and generative site of production of identities, knowledge and art. Dancers sing, juggle, ride bikes, imitate circus animals, manipulate objects, and dance. Sometimes they do almost nothing, daring us to stare or to question what is real. In their playful experimentation bodies and bodily talents are revealed as well as hidden. Two of the five performers have bodies that might be described as disabled, differently abled, non-normative, crippled or different. Everyone has a crutch, that is, a way of extending themselves with objects, tools, or other people to achieve things they wouldn’t be able to do otherwise. These humans seem broken yet undefeated. Together they build a queer world beyond the obvious, the norm, the rule.

The choreography or dramaturgy of this splendid provocation in the guise of a theatrical performance is not obvious. It’s more like a gestalt of performative actions, images and interventions. For most of the work there are multiple simultaneous events. A crisis of representation, of identity, is provoked by this crisis of choreography. The dancers demonstrate both virtuosity and banality. The five performers work alone, in duets and trios. Neither my notes nor memory of this densely layered performance recall any moment when all five were in the same game or image. The following descriptions attempt to resist a falsely linear chronology of the chaos-like multiplicity, simultaneity, and confusions that structure (and de-structure) the work.

Claire enters, most of her body and head covered in some kind of over-sized, insulated welding suit. In her gloved hands she holds crutches like enormous tweezers carrying a plush bunny, as if it is toxic and must be kept away from everyone. Funny. Strange. Then I notice the only parts of her body that are visible: ankles and feet. Her feet are oddly flat and her ankles seem to dislocate or relocate with each step. Her walk is fragile and I realize that I’ve never before seen her walk without the aid of crutches.

In her body-distorting fat suit Maria swerves madly on roller skates, narrowly missing people, objects, and wiping out. At a blackboard she writes, “He hides in exposure. Love is a structure. I respect Spinoza. Me too. OMG.” Standing (in roller skates) on a table, Scaroni alternately sings and lipsynchs a song that includes the lyrics, “Only in my dreams.” Her camp entertainment is unexpectedly intimate. Maria’s skates prevent any stable position, keeping her always poised at the edge of danger or momentum. Later she returns to the blackboard, now naked, to write, “What scars you? How do you pretend to be strong? Did you sabotage my roller skate?”

After an (amateur) strip to underwear, Jörg appears in a red riding hood cape. Suddenly he jumps into a wide stance with bent knees. The cape opens to reveal a fuzzy pink bunny slipper covering his genitals. Legless David Toole’s muscular upper body seems to collapse into itself, diminishing his non-chair height to below Müller’s crotch. David reaches with his rubber-gloved hand to pet the bunny codpiece. As he continues to stroke the bunny, Jörg slaps his hand away. Bad boy! We laugh and squirm. The interaction is so queer, so peculiar, so gay, complicated and delighted by reading these guys as hetero dudes engaged somehow innocently in a contradiction of queer fetishes, rubber and plushy. Touch. Don’t touch.

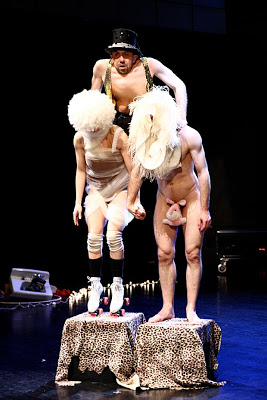

I nearly jumped to my feet to applaud the sublime circus-like act in which David plays both trainer and animal. He is wearing top hat and vest, and something animal print. The music is spaghetti western. Walking on his huge hands and powerful arms, David arrives on each block as if we should applaud. Ta da! See the trained cripple, I mean dancer, I mean freak, approach the wary audience. See how he balances and never falls. Maria and Jörg enter on hands and knees. Big cats. David commands them, pets them, and begins to climb onto their bodies. Slowly they rise, until they are standing (Scaroni still in roller skates!) on the blocks. Toole has continued to climb, to balance, until he is perched above their heads, his hands on their shoulders. Extraordinary. Bizarre. Edgy. Is the image more dangerous or unstable than the physical feat? The descent is controlled, awkward, and precise. In a hug, Maria carries David, and she skates them off stage.

In

Dances for…

Jess stages his most frequent practices: reading books for grad school and endurance bike riding. During a period of 15 or 20 minutes Curtis, geeked out in full lycra bike wear, rides a fancy road bike that powers a string of lights. He rides and rides. The action is vigorous. The impact almost ridiculous. He goes nowhere. The lights are meager. But his energy builds with the work, the sound of his labors increase via breath and spinning back wheel. With this increasingly intense action Curtis anchors the project.

Curtis, Gómez-Peña, and the collaborative performers have crowded this work with obsessions, desires, fears, taboos, fetishes, and archetypes. They’re playing with objects, playing with themselves and each other, playing with us, playing with ideas and representations, playing with identity, playing with bodies, playing with the con/fusion of real and imaginary. This serious and disciplined play informs a wisely crafted choreography of improvisations, situations, and sensations. The work is intended as provocation but does not shy away from entertainment. In the friction between contradictions Curtis and gang have generated significant warmth, raising the social temperature, daring us to playfully disrupt our own bodily fictions.