Hope Mohr Dance / Have we come a long way, baby?

The Bridge Project 2014:

ave We Come A Long Way, Baby?

Hope Mohr Dance in association with Joe Goode Annex

Sep 26, 2014

The Bridge Project 2014:

Have We Come A Long Way, Baby?

Hope Mohr Dance in association with Joe Goode Annex

Sep 26, 2014

From the program:

“For its fifth anniversary, HMD's Bridge Project presents Have We Come A Long Way, Baby?, a program that celebrates and explores a West Coast post-modern dance lineage through an intergenerational lineup of female soloists.”

Anna Halprin

The Courtesan and the Crone (1999)

Anna Halprin, one of the most innovative, experimental and influential of dance artists, performed a mime piece; a five minute dance-theater work wearing a Venetian mask that was a gift from her daughter and a floor-length gold cloak that she previously wore to the White House. 94 years old. Fragile. Eager to make contact. To move. To move us. To touch. I felt lucky to share this moment that vastly transcended the actual choreography and yet of course was deeply implicated in its embodied narrative and mimicry, desire and nostalgia, power and loss. Halprin's courtesan was articulate and unabashed. She presented the mask of a younger woman and the body that still remembers her, at least in gestural fragments. Her crone fluctuated between grief – what have I become? – and a calm resolve or affirmation. We applauded. Anna smiled and bowed and exited carefully, each step significant.

Simone Forti

News Animation (1980-current)

An improvisation about water, Syria, cockroaches, a baby... is also an improvisation about Simone Forti, aging, improvisation, politics, and art. A way or reading and re-reading the news, News Animation, since 1980, has modeled a creative process for bridging the many gaps between Forti's (and perhaps y/our) lived experience and the political realities presented and framed as news. White haired and 70 plus, she knows her body, how it can get to the floor and back up without excessive effort, how it feels.

Meandering movement – she reveals an artist looking and finding – but then the mood shifts sharply as she walks directly toward us, speaking, “So we're bombing Syria. And we don't know why. And they tell us it's to protect the homeland. (pause) The homeland.” It's easy to say that of course we should be talking about Syria today and of course we don't know how, especially in public. Forti accepts this ethical challenge gracefully. “We want the borders that we established after WWI to hold.” Is it her age, her quivering gestures, the humbleness of the situation (a small studio theater, an audience of dance people) that help us to see the tragic absurdity in this statement? With her head gently bobbing beyond her control, she gestures, “If I'm the map, Iran is on this side (right thigh), and Saudi Arabia is on this side (left thigh), and Iraq is here (hands form a triangle over her crotch).” I'm reminded of Deena Metzger's late 70s or early 80s efforts to map the world onto the body, a feminist imaginary that recognizes the many resonances between one's body and one's world, between one's perception and one's projection. Considering her own body/mind/self, Metzger asked questions like, where are my borders open and where are they fortified? Where is there starvation or drought? Where are the rivers dammed and where are the war zones?

Forti emerges from a similar era of feminism and an art scene whose political critique of art and society led them to share creative process as “product” (Prioritizing “practice” as Arrington and Hewit might assert). For News Animation, Forti reads a newspaper and takes notes in the form of poetic journaling. In tonight's performance the notes were read live, an exposure of process but also a deepening of the material, revisiting it but from the past, rewinding time to reconsider the now. “Colonialism. I can never remember so I reach for my colon.” Her body grounds and recontextualizes language, perhaps patriarchy and its logic as well. Reading from a notebook, head bowed to the page, white hair vibrating with her shakes, she recounts a dream of power men and their penises and closed sexual circuits that exclude everyone else.

A dance with a white sweater and scarf shifts unexpectedly into a story of fish that know how to organize in solidarity and resistance. Forti is a gentle master. Using the tactics of innocent (or is it subversive) children's theater, she transforms the clothing into a snowy Montana horizon along her body (mountain), and then admits to failing to represent the milky way... Perfect and imperfect, her imagination always in process of both refinement and wilding, an ethical feminist artist researcher child whose failures are gateways to magic.

Lucinda Childs

Carnation (1964)

Performed by Hope Mohr

White chair. Black table. Red leotard. Blue jeans. Her right foot in a blue plastic bag. A kitchen sieve treated as an iconic or holy object. Carefully she constructs sandwiches from green sponges and pre-cut carrots that fit the width of the sponge. Color and form redux: Fluxus tasks, Dada disruptions, Judson deconstructions. Carrots ceremoniously inserted into sieve create an altar of orange radiance, then a crown when place delicately on her head. Many sponges are stacked vertically and one end inserted into her mouth. The mask is further manipulated by cramming the fanned gaps of the sponges with the carrots from her crown. The game ends by spitting everything into the blue bag removed from her foot.

At the back wall she does a headstand. In precarious balancing she performs a circus act with socks and a white sheet and she disappears. Ta da! It recalls certain actions/images in Xavier LeRoy's Self Unfinished, created 34 years later.

She captures air in the plastic bag and it stands unsupported. Another circus act with magic fully exposed and yet it's still magical, that is, whimsical, unexpected, and previously unimagined. She looks at it. Stomps it. Smiles. Proudly. The smile turns on and off. Then she cries. Steps away. She performs tasks with arbitrary rules that must be obeyed. If this isn't the essence of art, it's one of them.

I propose this work for an Izzy: best reconstruction of 2014!

Hope Mohr

s(oft is) hard (2014)

Performed by Peiling Kao

Sound by Ben Juodvalkis, Video by David Szlasa, Costume by Keriann Egeland

We hear the sound of writing, by hand. A mix of knocking and scratching. Peiling faces away from the audience but her face, in close up, is projected, large, as if staring back at us. She is wearing black tights and a blue crocheted top. A voice over, Hope I presume, tells of writing 89 journals in 20 years. She recites specific dates but not the entry that follows... After reading through the journals while making this piece, the voice tells us that she recycled all of them except the first and the last, numbers 1 and 89. I believe her and vow to hold on to my old journals even tighter.

There is a more complicated relationship between text and movement, or language and embodiment, than in the previous works tonight's program. More dates. More sounds of writing. More silences. More shapes and gazes and self-touching gestures and other dancing movement. Minimal piano accompanies the continued chronological progression of dates...we're in the 90s...then 2000s. Video is intermittent. We switch from face cam to feet. Peiling's breath becomes the dominant text as her movement increases in vigor. Today's date. Tomorrow's date. She rolls and jumps repeatedly. A virtuosity that impresses, viscerally. On her back, the lights fade, slowly.

Resources:

Deena Metzger

I can't find the actual reference that was a radio piece from the 80s but here's her current work:

http://www.deenametzger.com/Home/home.html

Xavier LeRoy, Self Unfinished (1998)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G3rv1TeVEPM

PS:

I am an enemy of the slow fade to black at the end of a dance. Also the device of the blackout to begin a piece, to tell the audience that it has begun, and to allow the dancers to enter the space unseen (or the suggestion of unseen since I can almost always see and hear them). The framing of the stage or the theatrical moment with darkness is a cliché, a trope emptied of any specific meaning that carries more ideological weight than dancers in the US are taught to consider. In San Francisco I witness these devices at almost every concert I attend. In the “contemporary” dance scenes I frequent in Europe or New York, they are extremely rare, and when they occur they are more likely to be conceptually integral to the work.

This Is The Girl / Funsch Dance Experience, Sep 2014

Choreographer Christy Funsch enters to give the (now) compulsory pre-show announcement that unnecessarily frames dance performances in SF... but with a twist... when we realize that the announcement is (integrated into) the performance. Information about exits and cell phones erodes into awkward silences and unfinished statements, until finally Funsch states, “I am nothing” and exits as if lost... This opening action reveal's Christy's dry (or is it wry?) sense of humor that threads through and sometimes even structures her work...

This Is The Girl

Funsch Dance Experience

Sep 12-14, 2014

Dance Mission, SF

Observations and opinions by Keith Hennessy

followed by a comment by Christy Funsch

Choreographer Christy Funsch enters to give the (now) compulsory pre-show announcement that unnecessarily frames dance performances in SF... but with a twist... when we realize that the announcement is (integrated into) the performance. Information about exits and cell phones erodes into awkward silences and unfinished statements, until finally Funsch states, “I am nothing” and exits as if lost... This opening action reveal's Christy's dry (or is it wry?) sense of humor that threads through and sometimes even structures her work.

A woman in a red dress plays electric guitar with five young, fit, multiculti, dancers. Christy and Nol (Simonse) are the seasoned performers in this work, sometimes exaggerating their “experience” by playing old farts who need help from the young whippersnappers. When they chat, the text and performance are so unforced. The audience relaxes. It's easy to laugh along and enjoy. Later Christy tells me that the conversation is improvised. I say it's like watching old friends play together. Super charming. Amid family tales of sisters and coming out, they talk about story versus nonlinearity and ponder the relationship between construction and imagination.

SF choreographers never got the memo that unison movement is “out” or at least should be questioned and not assumed as integral to dance making. But then I think about how many companies based in SF (at least 5, maybe 6...) employ photographer RJ Muna to make them look practically indistinguishable, their (wannabe) sexy lithe bodies revealing lots of bare skin, leaping. Add some flying fabric for extra drama. Neo-classical modernism thrives here. That's not what Christy's doing with her young dancers, but it's a meandering rant that follows my questioning of her use of synchronized ensemble movement. What is possible to communicate, invoke, or inspire with dancing and when is unison the best tool or sign for choreography?

The next section involved the Dance Brigade's Grrrl Brigade on Taiko drums, led by Bruce Ghent. I thought Bruce's role was perhaps too big for a young female empowerment project but my main experience was of the joyful power of the taiko, and the particularly feminist approach to taiko that the Dance Brigade, with Bruce's coaching, has brilliantly pioneered. I don't know whether it was the thrill of the precision drumming or the ubiquitousness of teen girls in daisy dukes but I didn't notice at first how short the girls' denim shorts were. But when I did, they distracted me. How does fashion happen? Can shorts be too short? And would I be a terrible parent of a teenage femme?

The young dancers help out the fake-old dancers and everyone plays together – electric guitar, taiko teens, big showy dancing. What does dancing do? It invites me to ponder issues of age and power, of gender and sexuality, of color and racism, of the relationship between individual and group, of the invisible exchanges and collaborations from which choreography emerges. Maybe a better question is, “what does dancing want?” or “what do dancers and dance makers want?” But maybe not.

Nol joined the quintet for encounters of touching and measuring. I'm writing this in Rome from notes I scribbled in the program's margins three weeks ago. And this note doesn't trigger any memories. I wonder how long I've been watching Nol perform... more than a decade I'm sure. He's a generous dancer who plays well with others in so many different contexts. I loved seeing him outside a sprawling warehouse in Oakland in the work of Mary Armentrout and I remember being provocatively surprised when I finally saw him in his own work.

My notes kinda fall apart. I noted three slow pods, cuddling but not ________ then simply “taiko + dance” and an observation about recurring cross generational themes that made me re-assess my earlier comment about Bruce and the Grrrl Brigade.

The emotional tone of the work coalesced with the entrance of a team of young girls from the SF Community Music Center's Children's Chorus. The vibe intensified – I don't know how to describe it but something was happening – to all of us it seemed – the energetic-emotional field intensified when Christy and Nol started dancing, fierce at first and then in unison. “Horses in my dreams...” the girls sang. Teens hung out in the back, looking out windows, and although the image was 'staged' it didn't feel fake. It just felt good, like how it's supposed to be, and I mean the whole thing, all of us, sitting there in the dark and light. The person beside me started to cry which simply seemed like part of the plan, or part of the potential of the plan, as if (Christy's) choreography is not a plan but an invitation for an experience to happen, inside and among us.

The song ended. A light, fast, repeating dance moved upstage, with one dancer downstage center focusing our gaze into a four-generational world of music and dancing, in the Mission, where many of us live(d) and work(ed). And this history of place and creativity, while delicate, seemed neither precarious nor exceptional but just right, just right now.

Response by Christy Funsch, choreographer of This Is The Girl

One of the most difficult decisions I made in my recent full-length work, This is the Girl, was how to costume the teenage women of the Grrrl Brigade (who accompanied several sections of the work on Taiko). I allowed the six 8-year old girls from San Francisco's Community Center (who sang to accompany the last section of the work) to dress as they wished-why wouldn't I offer the same freedom to the teeagers?

Perhaps because it isn't so simple. Questions of who is in charge and in control of their presentation in public beleaguered my wrangling. Do they realize that they stand on the brink of our culture's vapid insistence on objectifying them? They study dance and music (and some have for ten years or more), with Krissy Keefer's Dance Brigade, a crucial, strident collection of women who have pushed back against mainstream depictions of femininity for decades. Surely some of this counter-cultural politic has rubbed off? Why, then, when given the choice of costuming, did they all decide to wear revealing, tight-fitting clothing very similar to each other's and very much emphasizing their physiques?

Should I have asked them to wear pajamas? Or martial arts clothing?

Most disappointing to me is owning that when I was wrangling over this decision I did not set aside time to have this conversation with them. I should have made it as much of a priority as getting their music rehearsed. It also brings up for me a larger query which served as subtext for the work, subtext that was latent perhaps but nonetheless alive in my decision to assemble an age-diverse cast for the work. Is there a time when we realize our place in power's structure? Does this happen at different times depending on where you are in the structure? How does our confidence shift when we grow from young girls into teenagers? What happens when we come into sexual awareness and how can we cultivate autonomy in young women when it happens-not just inside the household but all of us, culturally? Is provocative dress a sign of empowerment or compliance with expectations and objectification? Is it the height of conformity or a bold act of rebellion and resistance?

I don't know and will now have to (sadly) file under "conversations that didn't happen." I was so focused on the power implicit in the choreography (what I call "who is lifting whom"), that I missed an opportunity to engage the extended cast in this troubling, rich discussion.

Bay Area Dance - 2008 - The West Wave Dance Festival

Equality. Free Speech. Democracy’s Body. The Bay Area. The West Wave Dance Festival. In the future everyone will have 15 minutes of fame. In the West Wave Dance Festival each choreographer had five minutes on the big stage at Yerba Buena. Three programs. Thirty-five companies. An equitable and representational form of democracy that celebrates a utopian correction to the cultural segregation of most of our daily lives. This kind of democracy is also championed by the Izzies (the Bay Area’s Isadora Duncan Dance Awards) and might even be considered a San Francisco or Bay Area ‘Value.’...

ALMOST EVERYTHING I’VE EVER WANTED TO SAY ABOUT BAY AREA DANCE BUT DIDN’T HAVE THE CHANCE

Keith Hennessy responds to the 2008 WestWave Dance Festival

August 16-24, 2008

Produced by Dance Art, Dancers’ Group, YBCA

Dance Wave 1, 2, 3

The Novellus Theatre at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

Equality. Free Speech. Democracy’s Body. The Bay Area. The West Wave Dance Festival. In the future everyone will have 15 minutes of fame. In the West Wave Dance Festival each choreographer had five minutes on the big stage at Yerba Buena. Three programs. Thirty-five companies. An equitable and representational form of democracy that celebrates a utopian correction to the cultural segregation of most of our daily lives. This kind of democracy is also championed by the Izzies (the Bay Area’s Isadora Duncan Dance Awards) and might even be considered a San Francisco or Bay Area ‘Value.’

Diversity is generally a white liberal idea. Multicultural ensembles, as well as arts spaces and festivals that offer multicultural programming, serve an audience that is primarily white, i.e., not diverse. This held true for this year’s West Wave festival. If diversity programming does not attract diverse audiences, what is its goal? What aspects of the West Wave festival were not compelling to local audiences? With each company having only five minutes on stage, the reason to attend was not to see a specific company but to be wrapped in a crazy quilt of found fabrics, to taste test from an international smorgasbord, to enjoy or be challenged by juxtapositions, comparisons, frictions, and resonances between companies. From this holistic or systems view the 2009 West Wave Festival was a delightful success. But if so few people want to experience this wide-angle portrait and if the blackouts between pieces symbolize cultural divides that no amount of stage sharing can bridge then should this form be repeated?

The intentional creation of multicultural ensembles (SF Mime Troupe, The Dance Brigade, ODC) has its roots in a radical critique of mainstream society’s institutional racism. These troupes emerged from 1960’s and 70’s counter-cultural contexts inspired by the radical left, lesbian-feminism, and a series of ruptures in the arts. During the turbulent 60’s the established powers that refused to defend Native American independence or Civil Rights were quick to fund Alvin Ailey as the #1 American cultural export. An image of African American inclusion contrasted the facts at ground level. Progressive and reactionary forces are continuously at play and depending on one’s perspective social justice is improving (Obama) or not (US schools, prisons). The white choreographers and audiences of the SF Ballet receive massive and disproportionate funding from both public and private sources. Simultaneously, there are people in several powerful positions in Bay Area arts funding and presenting who are deeply committed to equitable distribution of resources and increased visibility for minority and/or marginalized cultures.

A review written in the spirit of the West Wave Festival would give an equal amount of commentary to each company that performed. It might even give each group the same quality of praise and/or critique, interrupting any attempt to favor or privilege one performance over another. My response is more subjective, as evidenced already by a particular politicizing of perspective. I am a fan of postmodern strategies and critical of dance that seems either nostalgic or unquestioning of tradition.

There was a striking similarity to most of the 35 dances staged in the festival. Dancers entered in the dark. The lights came on to reveal dancers in a still shape. Dancers moved in time to music for somewhere between four minutes, thirty seconds and five minutes. And then, in an obvious relation to music or narrative, the dance ended with stillness (or a repeating movement), and a slow fade to black. The audience applauded.

Interruptions to this structure were infrequent enough to stand out as nearly daring even if they simply used other accepted choreographic tactics, like walking on in light (Smith/Wymore), beginning in the audience and then moving to the stage (Chris Black), or dancing as if there was no beginning or end (Amy Lewis).

I have been looking for a way to simply describe Bay Area or American dance that seems to ignore most of the innovations and experimentation of the past 50 years, since Anna Halprin and Cage/Cunningham through Judson, performance art, contact improvisation and even Sara Shelton Mann/Contraband. (Disclosure: I performed with Contraband from 85-94.) European dance writer Helmut Ploebst uses the awkward term “modernistic American post-post-modern” to contrast Bill T Jones, Stephen Petronio, and Neil Greenberg from their contemporaries in Europe including Meg Stuart, Jan Fabre, Jerome Bel, or Vera Montero. I think his term could also apply to several contemporary Bay Area companies including ODC, Deborah Slater, Stephen Pelton, Brittany Brown Ceres, Janice Garrett, and Leyya Tawil. But of course this kind of classification is mostly useless and unnecessarily divisive. Kathleen Hermesdorf’s group choreographies might fit this term but her duet work with musician Albert Matthias does not. Alex Kelty’s choreographic research projects interrupt many modernist notions but his dance for Axis shown in West Wave was an expressionist dance-theatre drama that could easily be classified as post-post-modern.

I apologize in advance to the 35 choreographers whose work I mention here. I use your creative labors to spark an eclectic critical commentary on tendencies in Bay Area contemporary dance (and beyond). Certain prejudices prevent me from experiencing your work as you intended. Seeing the performance and reading the program bios demonstrates each and every choreographer’s deep commitment to dance. From a deep well of dance-making experience I respect the deep commitment, personal vision, and years of hard work with inadequate resources that is embodied in each of the following dances.

Given the massive effort it takes to accomodate 35 companies sharing a single stage, each program ran remarkably smoothly, production values were high, and everyone looked great in lights designed by Michael Oesch. Congratulations to the producers, technicians, designers and dancers.

Dance Wave 2

Wednesday August 20, 7pm

To a striking song of acapella voice and clapping by Quay, Alayna Stroud began the evening with a dance on and around a suspended vertical pole. Bold sharp arm gestures punctuated a dance of moody poses. With Quay singing of an inability to let go of the pain, the dance ended with Stroud, high on the pole, spinning, inverted, holding on.

An ex-SF Ballet dancer now award-winning international choreographer, Robert Sund offered a trio ballet to Leonard Cohen songs. Leaping and spinning, Ryan Camou generated an energy that was not met by his partners-en-pointe, Robin Cornwell and Olivia Ramsay. The choreography and performance seemed more like an earnest study for young dancers than a finished work appropriate to this scale of venue.

Ankle-belled and brightly dressed in orange and green, seven dancers from the Odissi dance company Guru Shradha performed a ritual dance of slowly spiraling arms in lovely light. The group formations, always frontal facing and symmetrical, seemed to freeze the action within the confines of the stage, rendering it a visual event to be viewed rather than a spiritual event to be felt.

A trio of women in white danced an impeccably synchronized choreography of glances and head gestures. Choreographed by Wan-Chao Chang whose extensive cross-cultural training includes Balinese dance and music, There was like something that Ruth St. Denis dreamed of making but lacked the technical training to manifest. The work recalled a women’s Modern dance chorus from the 1920’s or 30’s updated with deeply embodied non-Western movement that could only be possible with the cultural migrations and fusions of the past thirty years.

Cynthia Adams and Ken James of Fellow Travelers Performance Group choreographed an absurdist romp that satirized martini culture, an easy target. The central image was a dancer (super compelling Andrea Weber) attached at the back by a long wooden pole to an enormous wheel. It looked like it a design by Fritz Lang or Hugo Ball. As she muscled herself to spin, the wheel circled the stage while martini holding dancers ducked or swerved to avoid being knocked over. Dancers traded clothes, Ken ended up wearing a dress, and Cynthia crossed the stage with a vacuum. No one noticed the woman-machine that kept it all moving.

In this festival everyone gets five minutes. That’s one image, one gesture, one relationship, one moment within a twelve-scene event. In this context Christy Funsch made a clear and subtle choice. Alternating curvy sensual gestures and sharp punctuating lines, Funsch slowly traversed the stage. The music, like the dancing, was emotional but not dramatic. Reading her body’s writing from audience left to right, I was drawn into the choreography, and therefore the body, and thus an intimate encounter.

The most memorable sense I have of Deborah Slater’s Gone in 5 was the joyful meeting of full-bodied dancing (big leg circles, tumbling off tables), bluegrass with a driving beat, and untamed red hair. A female trio in red wigs and black dresses seemed to enjoy every bit of their five minutes but I missed the conceptual/intellectual engagement that inspires most of Slater’s dance theatre. By this point in the program I wondered if the five-minute rule and the late summer scheduling encouraged a lite touch, or discouraged more serious inquiry.

Innovators of the American Tribal style of belly dance, Carolena Nericcio and Fat Chance Belly Dance began with controlled undulations of arms, spine, pelvis, and belly. In super colorful costumes they gathered speed, energy, and volume, with finger cymbals rocking, into a final gesture of accelerated spinning, their skirts dancing like flames.

Amy Lewis’s Dada meets Judson happening was a delightful revelation. Titled and performed as a series of tasks, 35-40 performers filled the stage playing cards, wrapping gifts, stacking blocks, juggling, stuffing balloons in their clothes, and jumping rope. A trio of musicians played live. Two dancers in wheelchairs snaked through all the activities linking them like unraveling yarn. Someone read kid’s books. An actual kid did something else. Andrew Wass and Kelly Dalrymple, wearing their signature white shirts, red ties and black pants, repeatedly lifted each other from a chair at center stage. Others ran into the audience distributing free gifts. And that’s not all that happened! The stage came alive. The audience woke up. Reviewer Rachel Howard wanted to flee the theatre. People wanted to know what was going on. (What the heck was going on?!!) People wanted it to end. People wanted a gift. This is the piece that made it worthwhile for me to leave the house and risk my attention on dance. Thank you Amy.

Hip hop renaissance woman Micaya served up a celebration of booty that recognized its own hype and played the hip hop game with a self-awareness that the suckers on MTV can’t conceive. The choreography flirted with the music’s butt-worshipping lyrics, as if the body (booty) could talk back, call and response. Her diverse young crew, SoulForce, jumped through musical genres and even crumped to classical.

As soon as SoulForce arrived on stage, their friends (friends of hip hop) started calling out to the dancers in a kind of direct feedback that Rev. Cecil Williams referred to as “listening Black”. Dance styles are not the only ways that dance marks cultural difference. Audience response differs as well. Do we “listen Black” or “White”? Do we enter ritual spaces, times and trances or do we observe with fourth wall intact? And if we have a preferred style of response, is it appropriate to jump forms, or do we stay obedient and respectful of cultural norms? Some of us experience everything on the proscenium stage, from ballet to Afro-Peruvian, hip hop to performance art, as post-colonial and post-European. Are there any traditions that have escaped colonial conditioning? There is a difference between shared (diverse) and universal (we’re all the same). I wonder if by foregrounding the equitable sharing of space by diverse communities we exaggerate difference and emphasize borders, preventing the awareness of the universal fact that we all dance.

Kara Davis made one Tuesday afternoon… for a group of young ballet dancers from (I assume) the LINES ballet school. Eleven dancers moved from whole group movement to duets in which the dynamics of shared weight spoke to human connection and mutual influence. One falls and domino ripples of weight pass through the group. It’s easy to fall into the trap of treating young or student performers as the adults they want to become. Davis artfully avoids this trap by leading these ballet bodies into relaxed weight and playful encounters. As well the simple costumes of nearly monochrome brown street clothes helped a more innocent sensuality emerge. The minimalist bluegrass score by Gustavo Santaoalla well supported the piece.

Kumu Hula (hula teacher) Káwika Alfiche and several of his students performed A Goddess with live singing and drumming. The work began as a solo invocation within a circle of light. The fabulous costumes involved big full skirts and circles of what seemed to be dried grass or brush around their ankles, wrists and head. The headpieces were like organic halos, bursts of energy extending in all directions. The program notes inform that the dance tells a dramatic story of volcano goddess Pele’s youngest sister. The movement was mostly front facing and synchronized and I lacked experience to follow any gestural or energetic narrative. What I could sense was cultural pride through an attention to visual, sonic, and gestural craft.

In DanceWave 2 there were nearly as many people on stage (partly due to Amy Lewis’ cast) as there were in the audience (approx. 100). Why aren’t more audiences attracted to this programming? Is it so tough to convince friends or colleagues from particular (dance) communities to see you perform if you’re only on for five minutes and sharing the stage with eleven other companies that do not share the same music and dance culture? I think that if the tickets had been $5 or free with a request for donations, (instead of $25 with a $7 service charge), the producers could have doubled or tripled attendance with no loss in box office income. But that doesn’t answer the larger question about what compels people to attend or avoid contemporary dance performances in any style.

Dance Wave 3

Wednesday August 20, 9pm

Working in both San Francisco and European dance contexts causes some dissonance in my perception. In the Bay Area we accept overt religious practice in the form of folkloric songs and dances as a normal occurrence. In Europe this would be considered highly unusual, either ridiculed as naïve or witnessed from a non-believing distance. I have never experienced what we unfortunately call Ethnic Dance in a contemporary dance context in Europe unless the dance/music forms are in an experimental encounter with European forms, or the forms themselves are being questioned or deconstructed. Every time I refer to my work as ritual (and I do), a European brow gets wrinkled. Still I question the language of god and religion in our work, especially as we advance towards a presidential election in which every candidate feels compelled to end their speeches with an emphatic, “God bless America.”

Aguacero is a Bomba company directed by Shefali Shah. Focused on Afro Puerto Rican Bomba the company sincerely describes their work as connected to basic folk religion practices: healing, ancestor worship, embodying the natural world, and initiating youth in traditional practice. Their work is a syncretic encounter of West African cultures filtered through the Caribbean while reframing Spanish colonial dresses, shoes and language. At Dance Wave 3 they performed Hablando con Tambores a dynamic skirt waving dance that surfed the fast-paced, joyful wave created by three drummers and four vocalists. After a lively solo, a second woman came on stage in a competitive/collaborative face-off of tightly patterned skirt tossing, moving so quickly that my eye memory retained traces of circling and spiraling fabric.

Like her Ballet Afsaneh colleague Wan-Chao Chang (DanceWave 2), Tara Catherine Pandeya has cross-trained in several non-Western dance forms and traditions. In a dance of circling hands and micro percussive movements of shoulders and head, Pandeya danced in a sensual world evoked by the music played live by the trio Marajakhan. The traditional Uyghur music and the long braids attached to Pandeya’s hat recalled the work of Ilkolm Theater (Uzbekistan) who performed the gorgeous epic Dance of the Pomegranates at Yerba Buena earlier this year. Both performances evolve from diasporic Central Asian Turkic cultures.

Alex Ketley in collaboration with Rodney Bell and Sonsherée Giles of Axis Dance Company created a tense and intimate dance drama. Punctuated by quick gestures and sudden conflict the lovers seemed caught between intense attraction and secret fears. The dancers’ intimacy with each other’s bodies further demonstrated the struggle of any two people to connect. In this case the two people had to cross the divide between man and woman, as well as between a person who walks on feet and legs and another who travels by wheelchair. When Bell fell backwards to the floor, supported by Giles, we realized that he was fully strapped to his chair and could now crawl like a snail with house attached until he muscled his way upright. The piece ended the way it began and why not? Most couple encounters circle through familiar territory.

Brittany Brown Ceres choreographed Shade a quintet of women bound in a space defined by a rectangle of light. The work alternated synchronized and solo movement with a variety of lifts to a score of uninspired contemporary techno. An unfair question blocks my vision. “Why are they dancing like that, working so hard with such tired vocabulary and choreographic assumptions?” This question only reveals my inarticulate frustration. Also it seems too specific about dance ceres (whose work I’ve never seen before) when in fact I ask it all the time when seeing post postmodern Bay Area dance. In the program text Ceres tells us that Shade was “crafted in public spaces to study landscapes which are designed to substitute for psychological balance and to unlock descriptive communication made of movement instead of words.” The gap between their craft and my experience was overwhelming.

The strangest work in the West Wave Fest was Brooke Broussard’s Moving The Dark. A solitary figure in black unitard, complete with hood, moved continuously in rhythmic patterns of extended sweeping limbs and undulating spine. In some contexts this costume and this action would cause uproarious laughter but here it was only weird, as in otherworldly. Three lengths of blue carpet were unrolled to mark the space into a geometry of lines and triangles but the choreography seemed to ignore these differentiated spaces, so after a couple of minutes I did the same. Six other dancers in three pairs completed the cast of this surreal-psychological modern ballet. Blackout. We clap. Then we hear a loud scream.

A woman’s voice is heard from the balcony. Some pop song I can’t name. “I’m gonna make a change in my life.” Then singing erupts throughout the well-lit house. The singing, by choreographer Chris Black and company, was charming as if we caught these citizens singing along with headphones on a rural trail or alone in their apartment. Moving towards the stage one of the performers faces the audience from the front row and sings only the first half of U2’s “And I still haven’t found (what I’m looking for).” A repeating motif of “change” of course recalls Obama but it is only afterwards that I find out that the piece is entitled Headlines and includes found gestures from print media with a fractured medley of pop music. Musical encounters between the performers grew increasingly complex, mashing one song against another, or everyone briefly singing the same song. Counting aloud, Michael Jackson’s Man in the Mirror, and little dances of borrowed shapes in absurdly out of context scenarios, became a virtuosic arrangement and performance of everyday life. The emotional power of this piece was a surprise. What seemed like a formal intervention and a cute referencing of pop culture became an impassioned cry for renewed meaning and solidarity. Wow.

Tango Con*Fusion offered a round robin of tango duets danced by an ensemble of six women betraying (they call it bending) the gender roles of traditional tango. Bay Area values have evolved to a point where bending gender and queering tradition is neither radical nor compelling. The dancing seemed polite, lacking the intimacy and tension that tango often evokes. I was reminded of Terry Sendgraff’s aerial dance company in the 80’s embodying a (lesbian) aesthetic that avoided competition and celebrated equal partnership. You might need to check your punk rock at the door to be able to enter the best of these egalitarian worlds.

Through Another Lens by Sue Li Jue is a modern ballet that confronts the legacy of the Vietnam War within a body that is both American and Vietnamese. The sound score succeeded in blending two distinct voices: a blues text by an American vet underscored by traditional Vietnamese folk music. Soloist Nahn Ho is a strong dancer whose spiral falls, clear shapes, and sudden turn to the audience dared us to witness him, a young man pushed to the limit by the political tensions that he embodies.

Second generation South Indian dancer and choreographer Rasika Kumar crafted the festival’s most overtly political piece. Gandhari’s Lament represented the story of the blind mother of 100 sons who were all killed in the Great War of the Mahabharata. With ankle bells marking every percussive step, Kumar’s powerful dancing used both abstract and mimetic movement to communicate a mother’s grief. Her bitter, closing curse could as easily be directed at today’s murderers.

Zooz Dance Company’s En Route opened with a gorgeous solo by Jessica Swanson in a backless top that highlighted her amazingly articulate back and hips. The fusion dancing of Zooz, co-choreographed by Jessica McKee, features ensemble Middle Eastern dance that is super precise and seductive. Their skirts, especially the boa-like trim, did not meet the quality of the dancing.

If an internal voice demanding “Why? Why?” prevents me from seeing most Modern dance made by contemporary choreographers, the volume elevates to near screaming when I’m watching modern ballet. Liss Fain’s Looking, Looking was another of the festival pieces that seemed like a study for young ballet students. How did these works get curated over the sixty choreographers who got turned down? Was there a category for student works? Or did these pieces represent the best of the ballet applications? In Fain’s work two men and five women in sexy black shorty shorts danced for five minutes to Bartok’s dramatic Concerto for Viola. There were lifts and arabesques; the dancing was neither stupid nor compelling.

Dance Wave 1

Thursday August 21, 9pm

Charlotte Moraga restaged and performed an original composition by Kathak icon Pandit Chitresh Das. The dance basically manifested its title, Auspicious Invocation. With liquid wrists, crystalline forms and an open expressive face, Moraga began in a circle of light, dancing her invocation to the four corners. Properly concluding the ritual, she ends with a bow. Moraga is an excellent dancer who has been immersed in this form for 17 years.

But what does it mean to wear a sari or Indian costume on stage in San Francisco? What relevance or resonance does a contemporary audience appreciate when watching traditional ritual dances? What combination of training and inspiration might result in a local Akram Khan? Someone who masters Kathak and subjects it to contemporary and global questions of performance? Someone who no longer feels responsible to represent a nostalgic or idealized cultural representation? Similarly what social context might encourage an African American dancer in the Bay Area to dare the kind of genre-busting performance of Faustin Linyekula? Someone whose expression of African-ness is dependent neither on folkloric tradition (pre or post slavery) nor on the specifics of urban Black cultures? I wonder what might happen if some of the local ‘ethnic’ companies abandoned representational music, costumes, and static ritual forms. I have been inspired by the complicated revelations of Khan, Linyekula, and other companies directed by non-Western artists traversing the borders of genre, ethnicity and culture, reframing ritual and spectacle for today.

Recent Bay Area resident Erika Tsimbrovsky crafted an evocative teaser of visual dance theatre that suggested we keep an eye towards further projects. Paper gowns that ballooned around the dancers as they dropped suddenly and a scratchy recording of a slow turning music box evolved a performance language sourced in image and memory. The dancers hid inside the dream space of their skirts, and two of them birthed themselves naked as the lights faded.

Sheldon B. Smith and Lisa Wymore made a smart, hip little dance generated from YouTube. Imitation, lip-synching, and multiplying the action via ensemble movement heightened our attention to the found sources and challenged a reconsideration of live performance’s relationship to online videos. What does it mean when highly trained dancers are viewed by an audience of 100 or 200 when non-professionals can be viewed by 3 million? Not only is YouTube a bigger performance archive than we could ever have imagined, but nearly all of YouTube’s most viewed videos involve dance or bodies in performance. Too many of the Dance Wave artists entered in the dark and held a static pose as the lights came up, so it was an unintentional and pleasant intervention to have the Smith/Wymore quartet walk onto the stage with the lights on.

In Mary Sano’s Dance of the Flower a woman’s head floats above a massive parachute skirt, under which we assume many dancers are hidden. To Bach’s cello the skirt begins to breath. I’m in a retro shock. Really retro. I’m thinking Duncan, perhaps after Fuller. This is neither an innovative skirt dance like Fuller’s nor a well-researched prop piece that recalls Mummenschanz or Momix. It’s more like a children’s theatre game evolved from metaphoric, expressive early Modern dance. Emerging from the skirt we are presented with a lovely poem of skipping women in Duncan-style, Greek-inspired tunics. (How many companies in this festival are all-women?) Sano, a third-generation Isadora Duncan dancer, choreographs under the influence of a series of assumptions about nature, women, dance, bodies, and flowing fabric without any recognition of the nearly 100 years of challenging and rewriting those assumptions.

Most Bay Area dancers work with such a poverty of resources (money, space, time, scheduling, management) that it is a marvel that there were nearly 100 companies applying to be in this festival. Nonetheless the lack of engagement and risk with visual design, especially light and sets, is often disappointing. This is as true for the last ODC concert that I attended as it is for most of these five-minute wonders. Dandelion’s Oust (excerpts) began with an odd solo backlit by an upstage performer with a handheld instrument, while a woman at a microphone laughed. The light shifts to another dancer who writhes, falls, twitches and freezes. Unfortunately this is neither Eric Kuyper’s strongest work with the company nor a great example of why we ought to experiment with light. But Kuyper continues to intervene with tradition, challenge conventional assumptions, and craft risky interdisciplinary experiments.

Smuin Company resident choreographer Amy Seiwert created Air a ballet pas de deux featuring Jay Goodlett and Tricia Sundeck. These dancers have considerable professional experience compared to the ballet dancers in Programs 2 and 3 which made this dance all the more disappointing with its lack of risk and insistence on neoclassical vocabulary and stale gender roles. The crowd was loud and vocal with praise. SF Chron reviewer Rachel Howard thought it was the best of the fest. I’m sure that Goodlett is a fabulous dancer but at Trannyshack, SF’s legendary drag club, he would be referred to as a ‘man prop’ (the male as functional object in service of the “female”). In diva culture this is not necessarily an insult.

Charya Burt’s Blue Roses reimagines Laura from The Glass Menagerie as a Khmer princess trapped in her own world. Wearing traditional Cambodian clothes Burt knelt in a circle of light, her wrists held at a sharp 90 degrees, palms pushing out, her fingers reaching well beyond their physical length. Despite the specific cultural invocation of gesture, costume, music and light projection Burt avoided mimetic acting in favor of detailed and articulate physical expression. Her intense presence and sensitivity were so palpable that even the subtlest of wrist and head movements seemed to charge the space around her. Similar to the slow intensity of early Butoh or Deborah Hay’s cellular movement the audience could either be bored to sleep or provoked into a radical encounter with the present, presence. I was impressed, touched.

Nine bodies in white, on their backs, marking the diagonal. In waves of canon the dancers of Loose Change pulse into and up from the floor. Choreographer Eric Fenn’s vocabulary reveals itself slowly in fragmented reference to break dance, hip hop and more. Percussion-based group movement proves this crew is the strongest large ensemble of the festival. Invoking a future city of dance monks the team falls into place remaking the opening image.

Another transition between companies. Another attempt at discreet set up in soft blue light followed by a black out, followed by lights up on dancers in stillness. Would it hurt to reveal the action, skipping the blackout and the precious stillness? Does the stage have to remain this nostalgic place of magic? How did the dancers get there? I don’t know they just appeared in gorgeous light and then started dancing.

I’m curious to see more work by Limbinal a young collective of artists directed by Leonie Gauthier. For their five minutes they presented INside which featured two man/woman duets, one on a table, accompanied by live cello. The work on the table, the mutual lifting, and the increasingly dramatic cello suggested a meeting of Scott Wells and Sara Shelton Mann in a chamber ballet.

Women lifting men ought to be more common in 2008 but its only other occurrence in this festival was with Wass & Dalrymple in How many presents… Contact Improvisation began in 1972 with an intention to democratize (remove the hierarchies from) the duet. But this is only one of the aspects of the postmodern dance ruptures that seem generally absent in Bay Area contemporary dance.

Luis Valverde (choreographer) and Eleana Coll gave a rousing presentation of Peruvian Andean dance. She, fabulosa in pink satin and white ruffles. He, dapper in blue suit, black boots, woven belt and wide brimmed white hat. Hankies revealed in their right hands, they begin to court each other. Indigenous footwork in colonial drag, they dance a timeless seduction of approaches, smiles, spins, and retreats. Their steps are rhythmic and light. The music alternates between symphonic and a military snare. These are handsome people and we want them to get together. When their faces pause almost touching, almost kissing, I want to cheer. The steps increase to skips but she never loses her coy cool. Now the hips are marking time more than the feet. A big energetic finale, racing against the music and they freeze, together. Big applause.

A voiceover instructs us to turn on our cell phones and invites us to document the dance. On stage are two men and one bride. The audience starts snapping pics. And thus begins Snap a work by Jenny McAllister for Huckaby McAllister Dance. A long tulle train attached to one man, when pulled, drags three pink dressed ladies onto the stage. The voice clowns our habit-obsessions with phones and the documentation of every waking moment. “Keep the truth safe from time. Isn’t that beautiful?” For a while this is physical comedy via ensemble dancing. Then the voice talks about grandparents in Minsk and the only photo in which no one smiled. “Bubby says it was just like that.” With efficient craft the weight of history is invoked and the simple social satire becomes only a preparation for a more intimate touch to occur.

Somei Yoshino Taiko Ensemble closed the evening with a fusion performance in which the dancers were the musicians, and the dance was an enactment and embellishment of the musical score. Four drummer/dancers moved around and within a circle of large and small drums. Sharp strikes from one arm. Boom! The other arm shoots vertically to the sky, extending its line with drumstick in hand. Quick shift. Boom! The energy ebbs and flows in a continual flirting of yin and yang carrying marked by stark freezes and silences. Synchronized activity amplifies the sound in such a concrete way: more drummers, more force, more sound. The pace increases towards a quick finale. The final gesture’s silence is the loudest action of it all. And they drop, disappearing into the center of the drums.

In a film clip shown at the Nijinsky Awards in Monaco a French interviewer asks, “WHAT IS dance to you, Mr. Balanchine?" The response was, "just dance."

Jess Curtis / Gravity • Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

The stage is filled with the remnants of past performances, stuff that seems to have lost either its meaning or function. Objects from theater prop rooms: mannequin parts, black cubes, an old fridge, a child’s desk, a vintage gurney, a bike, a mirror, and even the kitchen sink, ba da ba. This is the trash of representation, stuff that looks like or evokes or locates… The appearance of the sink suggests a hint of vaudeville, that US American entertainment fusion of dance, comedy, circus, sideshow, and cultural performance...

Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

(Preview excerpt)

Jess Curtis / Gravity

February 28, 2010

Presented at CounterPULSE (San Francisco) as part of Gravity’s Intercontinental Collaborations 4.

Created & performed by Maria Francesca Scaroni, Jörg Müller, Claire Cunningham, David Toole, Jess Curtis and dramaturg/provocateur Guillermo Gomez Peña. Conceived and directed by Jess Curtis.

The stage is filled with the remnants of past performances, stuff that seems to have lost either its meaning or function. Objects from theater prop rooms: mannequin parts, black cubes, an old fridge, a child’s desk, a vintage gurney, a bike, a mirror, and even the kitchen sink, ba da ba. This is the trash of representation, stuff that looks like or evokes or locates… The appearance of the sink suggests a hint of vaudeville, that US American entertainment fusion of dance, comedy, circus, sideshow, and cultural performance.

Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

includes all of these elements, but under the influence of contemporary dance and performance these elements are either reduced to abstract essence or maximized into camp excess. The mashup of these tendencies - towards essence or excess - defines the field of play for this team of improvisers.

By referring to the bodies as Non/Fictional, Curtis emphasizes the impossibility of denying the fiction within nonfiction, the imaginary within the real. The slash that interrupts the more commonly used ‘nonfiction’ intervenes on a simple reading of nonfictional as non-imaginary, not-pretend. The bodies in this carefully constructed mess recycle and repurpose objects as easily as personae, changing costumes and attitudes, wigs and positions. In Dances for… the body is real is a theatrical construction is a performance is an unstable and generative site of production of identities, knowledge and art. Dancers sing, juggle, ride bikes, imitate circus animals, manipulate objects, and dance. Sometimes they do almost nothing, daring us to stare or to question what is real. In their playful experimentation bodies and bodily talents are revealed as well as hidden. Two of the five performers have bodies that might be described as disabled, differently abled, non-normative, crippled or different. Everyone has a crutch, that is, a way of extending themselves with objects, tools, or other people to achieve things they wouldn’t be able to do otherwise. These humans seem broken yet undefeated. Together they build a queer world beyond the obvious, the norm, the rule.

The choreography or dramaturgy of this splendid provocation in the guise of a theatrical performance is not obvious. It’s more like a gestalt of performative actions, images and interventions. For most of the work there are multiple simultaneous events. A crisis of representation, of identity, is provoked by this crisis of choreography. The dancers demonstrate both virtuosity and banality. The five performers work alone, in duets and trios. Neither my notes nor memory of this densely layered performance recall any moment when all five were in the same game or image. The following descriptions attempt to resist a falsely linear chronology of the chaos-like multiplicity, simultaneity, and confusions that structure (and de-structure) the work.

Claire enters, most of her body and head covered in some kind of over-sized, insulated welding suit. In her gloved hands she holds crutches like enormous tweezers carrying a plush bunny, as if it is toxic and must be kept away from everyone. Funny. Strange. Then I notice the only parts of her body that are visible: ankles and feet. Her feet are oddly flat and her ankles seem to dislocate or relocate with each step. Her walk is fragile and I realize that I’ve never before seen her walk without the aid of crutches.

In her body-distorting fat suit Maria swerves madly on roller skates, narrowly missing people, objects, and wiping out. At a blackboard she writes, “He hides in exposure. Love is a structure. I respect Spinoza. Me too. OMG.” Standing (in roller skates) on a table, Scaroni alternately sings and lipsynchs a song that includes the lyrics, “Only in my dreams.” Her camp entertainment is unexpectedly intimate. Maria’s skates prevent any stable position, keeping her always poised at the edge of danger or momentum. Later she returns to the blackboard, now naked, to write, “What scars you? How do you pretend to be strong? Did you sabotage my roller skate?”

After an (amateur) strip to underwear, Jörg appears in a red riding hood cape. Suddenly he jumps into a wide stance with bent knees. The cape opens to reveal a fuzzy pink bunny slipper covering his genitals. Legless David Toole’s muscular upper body seems to collapse into itself, diminishing his non-chair height to below Müller’s crotch. David reaches with his rubber-gloved hand to pet the bunny codpiece. As he continues to stroke the bunny, Jörg slaps his hand away. Bad boy! We laugh and squirm. The interaction is so queer, so peculiar, so gay, complicated and delighted by reading these guys as hetero dudes engaged somehow innocently in a contradiction of queer fetishes, rubber and plushy. Touch. Don’t touch.

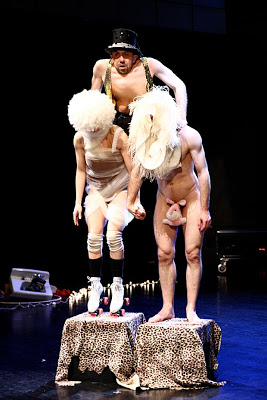

I nearly jumped to my feet to applaud the sublime circus-like act in which David plays both trainer and animal. He is wearing top hat and vest, and something animal print. The music is spaghetti western. Walking on his huge hands and powerful arms, David arrives on each block as if we should applaud. Ta da! See the trained cripple, I mean dancer, I mean freak, approach the wary audience. See how he balances and never falls. Maria and Jörg enter on hands and knees. Big cats. David commands them, pets them, and begins to climb onto their bodies. Slowly they rise, until they are standing (Scaroni still in roller skates!) on the blocks. Toole has continued to climb, to balance, until he is perched above their heads, his hands on their shoulders. Extraordinary. Bizarre. Edgy. Is the image more dangerous or unstable than the physical feat? The descent is controlled, awkward, and precise. In a hug, Maria carries David, and she skates them off stage.

In

Dances for…

Jess stages his most frequent practices: reading books for grad school and endurance bike riding. During a period of 15 or 20 minutes Curtis, geeked out in full lycra bike wear, rides a fancy road bike that powers a string of lights. He rides and rides. The action is vigorous. The impact almost ridiculous. He goes nowhere. The lights are meager. But his energy builds with the work, the sound of his labors increase via breath and spinning back wheel. With this increasingly intense action Curtis anchors the project.

Curtis, Gómez-Peña, and the collaborative performers have crowded this work with obsessions, desires, fears, taboos, fetishes, and archetypes. They’re playing with objects, playing with themselves and each other, playing with us, playing with ideas and representations, playing with identity, playing with bodies, playing with the con/fusion of real and imaginary. This serious and disciplined play informs a wisely crafted choreography of improvisations, situations, and sensations. The work is intended as provocation but does not shy away from entertainment. In the friction between contradictions Curtis and gang have generated significant warmth, raising the social temperature, daring us to playfully disrupt our own bodily fictions.

Scott Wells & Dancers, Men Want To Dance

What Men Want

Scott Wells & Dancers

May 31, 2009

Part of the 2009 SF International Arts Festival

ounterPULSE, SF

Scott Wells makes wonderful dances for men and women and sometimes he makes wonderful dances for men. Wells treats modern dance like a sport in a postmodern fusion of relaxed lyrical dancing, physical comedy, and surprisingly tender partner acrobatics. The leaps, catches, cat like landings and spiraling falls to the floor reveal the company’s roots in the dance known as contact improvisation...

What Men Want

Scott Wells & Dancers

May 31, 2009

Part of the 2009 SF International Arts Festival

CounterPULSE, SF

Scott Wells makes wonderful dances for men and women and sometimes he makes wonderful dances for men. Wells treats modern dance like a sport in a postmodern fusion of relaxed lyrical dancing, physical comedy, and surprisingly tender partner acrobatics. The leaps, catches, cat like landings and spiraling falls to the floor reveal the company’s roots in the dance known as contact improvisation.

What Men Want was a suite of four premieres, including two big works for an ensemble of eight men. In this meandering writing, I don’t review each piece. I’m exploring a few ideas, mostly about men dancing.

Wells’ work for men charms with a playful engagement of masculine clichés, anxieties and interventions. The work is so unabashedly straight, as in heterosexual, that it’s almost queer. I mean that Wells and his guys, regardless of their personal identities and affections, come across as straight dudes whose physical intimacy most often recalls the homosociality (aka male bonding) of a compulsively hetero locker room. At other moments of sensitive dancing and careful touch the choreography dares to intervene on hetero norms. We don’t expect sporty dudes to roll together quite so slowly. It’s queer in it’s intentional questioning of masculine performance. If there’s a weakness to this expansive view of hetero masculinity it’s the way that Wells’ choreography responds to nearly every gentle moment with a kind of defensive reaction of physical comedy, martial arts jokes, or just vigorous muscular activity. The choreographic rhythm is like a pendulum that inscribes a binary code, swinging from masculine to feminine, gentle to vigorous, sensitive to hilarious. This binary insistence is decidedly not-queer. The only device I contest is the ubiquitous ‘gay joke.’ There are a million variations - in dance, television, sports, Hollywood, advertising – in which two or more guys suddenly become aware of how intimate they’ve become, and the energy shifts, and the audience laughs. And that laugh, for queer boys, is too often a cruel laugh.

K. Ruby was a dance student and choreographer at Berkeley High 30 years ago. Recently, she told Linda Carr, the current head of Berkeley High’s dance program, how times had changed. With the addition of hiphop to the dance curriculum, it seemed to Ruby that more boys were dancing. She recalled that classes in the late 70s were predominantly female except for the occasional gay or soon-to-be-gay male. Carr pointed out that, sadly, today’s gender demographics were consistent with Ruby’s experience. And that’s the news in a town noted for its liberal and radical social politics, in a Bay Area known worldwide as a place for queer challenges to normative behavior. How much does gay anxiety and homophobia influence our dance cultures? Why is it so unusual for men to dance together in this culture we might call contemporary or post-European or even post-colonial? In Ballet, Modern dance, and the styles that follow, females are probably 80% of the practitioners, many in training since the age of four or five. Males start dancing later, take fewer classes, have significantly less competition for professional opportunities and consistently get more attention and resources. Despite the male dance superstars from Nijinsky to the Nicholas brothers, from Gene Kelly to Baryshnikov, and from Jose Limon to Savion Glover, dance – in the American popular imagination - continues to be gendered female, or feminine. Try to consider this while simultaneously and paradoxically noting that the most viewed YouTube video (100 million + hits) is a comic dance by Jud Laipley called The Evolution of Dance, AND the top prize for the past two years of Britain’s Got Talent was won by male dancers, who received millions of votes and even more YouTube hits. Diversity, a multi-racial, age diverse, all-male dance company, won this year’s prize and the 2008 winner was a 14 year old named George Sampson who performed a hiphop remix of Kelly’s Singing in the Rain. European and American boys and men are dancing but they’re still not taking modern dance classes in any great numbers. Scott Wells & Dancers operates within this larger social context of homophobic masculinity, gendered dance expectations, and special attention for dancing boys.

The two jewels of this oddly named evening of dancing were the smaller more formal works, Catch, a duet for two dancing jugglers, and Bach solo trio, danced by a solo woman and a trio of guys. I think I like Catch because of the lack of comedy. The duet connection between Aaron Jessup and Zack Bernstein (of Capacitor) was super sweet. All dance duets are about love, but some are less romantic than others. In this pas de deux with objects, the love was a shared loved. If I could call it Whitmanesque and not evoke sex, I’d call it the (chaste) love of comrades. They danced on and around each other’s bodies, always a red ball in hand, or traveling between them. As the work progressed, virtuosic ball tossing alternated with swirling lifts and spiral rolls over backs. Sometimes there was one red ball between them, but towards the end they each juggled five balls simultaneously, beginning and ending in perfect synch. Impressive. The dance ended the way it began, roles reversed, one man a landscape of body lying in a circle of light and the other walking the perimeter.

Bach solo trio opened with a short solo by Rosemary Hannon. Hannon (recently seen dancing with Non Fiction at The Garage) repeated a short phrase focused on the arms and torso. Hannon is tall, lean and articulate, a hyper-aware dancer whose long arms unfold in delicious detail to the ends of her fingers. Dancing in silence, her breath had a resonant presence. As she exited, the Bach began, and the men, Andrew Ward, Sebastian Grubb, and Cameron Growden, entered. As they repeated the same phrase as Hannon, I looked for difference and tried to determine which details were because of gender and which were due to the particularities of these bodies. The men were each and all more compact and dense than Hannon. They didn’t have the openness of shoulder flexibility nor the articulate detail in their fingers. Unlike Hannon, they hadn’t been taking dance class since early childhood. The openness and breath in their chests felt like a distant reminder of Hannon. The men really came to life in the curvy tumbling and floating handstands. There was a section of low spinning into and up from the ground, weight on and off of hands, that recalled the Brazilian dance/fight form capoiera. When they spun on one leg and dove to the floor I recognized the influence of Wells’ body or the Scott Wells that I remember from ten or fifteen years ago. Grubb especially reminded me of Wells’ unique style. The trio section ended with a marvelous thrill of lifts and tumbles, every landing unexpectedly quiet, like cats. Hannon returned, with arms and fingers so alive, her curly mane extending every action of head and spine, and somehow it was her female-ness in response to the trio’s male-ness that filled the space, and took this piece home.

The eight men in the ensemble make a delightful team. In addition to the five men previously mentioned, there is Rajendra Serber, Cason MacBride, and Ryder Darcy. The guys are generous with each other, authentically affectionate, and trustworthy in their attention and precision. Their joy of dancing is infectious and they love to entertain. Wells’ and his dancers are not hesitant to put on a show, to perform tricks, to make us ooh and ahh for a spectacular overhead lift and laugh with an unexpected yet intentional collision. Although they perform some synchronized movement, Wells’ laid-back choreography never enforces conformity. Some dancers shine more than others, but that is more an indicator of accumulated experience than of a lack of necessary talent. A fab flurry of athletic dancing closes the evening. Darcy runs up a wall and flips head over heels. Others run sideways to the wall and propel themselves into dive rolls onto a well-placed mat. Growden is a superb jumper with a loft to rival any high jumper. When he dives horizontally at the brick wall, two other men arrive to pin him, freezing the moment in time. Wells plays often with this kind of sustained time, floating bodies, pausing handstands, and full-body catches that linger, not so much frozen as floating, and then when released the falling weight becomes the momentum that drives the dance onward.

(A few months later I deleted a little joke of a line at the end that seemed to color the previous writing too much. There are comments by two of the men in the cast and another local choreographer - going further with questions of queer, masculinity, dance.)

West Wave Dance Festival 2008

ALMOST EVERYTHING I’VE EVER WANTED TO SAY ABOUT BAY AREA DANCE BUT DIDN’T HAVE THE CHANCE

Keith Hennessy responds to the 2008 WestWave Dance Festival

August 16-24, 2008

Produced by Dance Art, Dancers’ Group, YBCA

Performances – Dance Wave 1, 2, 3 – The Novellus Theatre at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

Equality. Free Speech. Democracy’s Body. The Bay Area. The West Wave Dance Festival. In the future everyone will have 15 minutes of fame. In the West Wave Dance Festival each choreographer had five minutes on the big stage at Yerba Buena. Three programs. Thirty-five companies. An equitable and representational form of democracy that celebrates a utopian correction to the cultural segregation of most of our daily lives. This kind of democracy is also championed by the Izzies (the Bay Area’s Isadora Duncan Dance Awards) and might even be considered a San Francisco or Bay Area ‘Value.’

Diversity is generally a white liberal idea. Multicultural ensembles, as well as arts spaces and festivals that offer multicultural programming, serve an audience that is primarily white, i.e., not diverse. This held true for this year’s West Wave festival. If diversity programming does not attract diverse audiences, what is its goal? What aspects of the West Wave festival were not compelling to local audiences? With each company having only five minutes on stage, the reason to attend was not to see a specific company but to be wrapped in a crazy quilt of found fabrics, to taste test from an international smorgasbord, to enjoy or be challenged by juxtapositions, comparisons, frictions, and resonances between companies. From this holistic or systems view the 2009 West Wave Festival was a delightful success. But if so few people want to experience this wide-angle portrait and if the blackouts between pieces symbolize cultural divides that no amount of stage sharing can bridge then should this form be repeated?

The intentional creation of multicultural ensembles (SF Mime Troupe, The Dance Brigade, ODC) has its roots in a radical critique of mainstream society’s institutional racism. These troupes emerged from 1960’s and 70’s counter-cultural contexts inspired by the radical left, lesbian-feminism, and a series of ruptures in the arts. During the turbulent 60’s the established powers that refused to defend Native American independence or Civil Rights were quick to fund Alvin Ailey as the #1 American cultural export. An image of African American inclusion contrasted the facts at ground level. Progressive and reactionary forces are continuously at play and depending on one’s perspective social justice is improving (Obama) or not (US schools, prisons). The white choreographers and audiences of the SF Ballet receive massive and disproportionate funding from both public and private sources. Simultaneously, there are people in several powerful positions in Bay Area arts funding and presenting who are deeply committed to equitable distribution of resources and increased visibility for minority and/or marginalized cultures.

A review written in the spirit of the West Wave Festival would give an equal amount of commentary to each company that performed. It might even give each group the same quality of praise and/or critique, interrupting any attempt to favor or privilege one performance over another. My response is more subjective, as evidenced already by a particular politicizing of perspective. I am a fan of postmodern strategies and critical of dance that seems either nostalgic or unquestioning of tradition.

There was a striking similarity to most of the 35 dances staged in the festival. Dancers entered in the dark. The lights came on to reveal dancers in a still shape. Dancers moved in time to music for somewhere between four minutes, thirty seconds and five minutes. And then, in an obvious relation to music or narrative, the dance ended with stillness (or a repeating movement), and a slow fade to black. The audience applauded.

Interruptions to this structure were infrequent enough to stand out as nearly daring even if they simply used other accepted choreographic tactics, like walking on in light (Smith/Wymore), beginning in the audience and then moving to the stage (Chris Black), or dancing as if there was no beginning or end (Amy Lewis).

I have been looking for a way to simply describe Bay Area or American dance that seems to ignore most of the innovations and experimentation of the past 50 years, since Anna Halprin and Cage/Cunningham through Judson, performance art, contact improvisation and even Sara Shelton Mann/Contraband. (Disclosure: I performed with Contraband from 85-94.) European dance writer Helmut Ploebst uses the awkward term “modernistic American post-post-modern" to contrast Bill T Jones, Stephen Petronio, and Neil Greenberg from their contemporaries in Europe including Meg Stuart, Jan Fabre, Jerome Bel, or Vera Montero. I think his term could also apply to several contemporary Bay Area companies including ODC, Deborah Slater, Stephen Pelton, Brittany Brown Ceres, Janice Garrett, and Leyya Tawil. But of course this kind of classification is mostly useless and unnecessarily divisive. Kathleen Hermesdorf’s group choreographies might fit this term but her duet work with musician Albert Matthias does not. Alex Kelty’s choreographic research projects interrupt many modernist notions but his dance for Axis shown in West Wave was an expressionist dance-theatre drama that could easily be classified as post-post-modern.

I apologize in advance to the 35 choreographers whose work I mention here. I use your creative labors to spark an eclectic critical commentary on tendencies in Bay Area contemporary dance (and beyond). Certain prejudices prevent me from experiencing your work as you intended. Seeing the performance and reading the program bios demonstrates each and every choreographer’s deep commitment to dance. From a deep well of dance-making experience I respect the deep commitment, personal vision, and years of hard work with inadequate resources that is embodied in each of the following dances.

Given the massive effort it takes to accomodate 35 companies sharing a single stage, each program ran remarkably smoothly, production values were high, and everyone looked great in lights designed by Michael Oesch. Congratulations to the producers, technicians, designers and dancers.

Dance Wave 2

Wednesday August 20, 7pm

To a striking song of acapella voice and clapping by Quay, Alayna Stroud began the evening with a dance on and around a suspended vertical pole. Bold sharp arm gestures punctuated a dance of moody poses. With Quay singing of an inability to let go of the pain, the dance ended with Stroud, high on the pole, spinning, inverted, holding on.

An ex-SF Ballet dancer now award-winning international choreographer, Robert Sund offered a trio ballet to Leonard Cohen songs. Leaping and spinning, Ryan Camou generated an energy that was not met by his partners-en-pointe, Robin Cornwell and Olivia Ramsay. The choreography and performance seemed more like an earnest study for young dancers than a finished work appropriate to this scale of venue.

Ankle-belled and brightly dressed in orange and green, seven dancers from the Odissi dance company Guru Shradha performed a ritual dance of slowly spiraling arms in lovely light. The group formations, always frontal facing and symmetrical, seemed to freeze the action within the confines of the stage, rendering it a visual event to be viewed rather than a spiritual event to be felt.

A trio of women in white danced an impeccably synchronized choreography of glances and head gestures. Choreographed by Wan-Chao Chang whose extensive cross-cultural training includes Balinese dance and music, There was like something that Ruth St. Denis dreamed of making but lacked the technical training to manifest. The work recalled a women’s Modern dance chorus from the 1920’s or 30’s updated with deeply embodied non-Western movement that could only be possible with the cultural migrations and fusions of the past thirty years.

Cynthia Adams and Ken James of Fellow Travelers Performance Group choreographed an absurdist romp that satirized martini culture, an easy target. The central image was a dancer (super compelling Andrea Weber) attached at the back by a long wooden pole to an enormous wheel. It looked like it a design by Fritz Lang or Hugo Ball. As she muscled herself to spin, the wheel circled the stage while martini holding dancers ducked or swerved to avoid being knocked over. Dancers traded clothes, Ken ended up wearing a dress, and Cynthia crossed the stage with a vacuum. No one noticed the woman-machine that kept it all moving.

In this festival everyone gets five minutes. That’s one image, one gesture, one relationship, one moment within a twelve-scene event. In this context Christy Funsch made a clear and subtle choice. Alternating curvy sensual gestures and sharp punctuating lines, Funsch slowly traversed the stage. The music, like the dancing, was emotional but not dramatic. Reading her body’s writing from audience left to right, I was drawn into the choreography, and therefore the body, and thus an intimate encounter.

The most memorable sense I have of Deborah Slater’s Gone in 5 was the joyful meeting of full-bodied dancing (big leg circles, tumbling off tables), bluegrass with a driving beat, and untamed red hair. A female trio in red wigs and black dresses seemed to enjoy every bit of their five minutes but I missed the conceptual/intellectual engagement that inspires most of Slater’s dance theatre. By this point in the program I wondered if the five-minute rule and the late summer scheduling encouraged a lite touch, or discouraged more serious inquiry.