Bay Area Dance - 2008 - The West Wave Dance Festival

Equality. Free Speech. Democracy’s Body. The Bay Area. The West Wave Dance Festival. In the future everyone will have 15 minutes of fame. In the West Wave Dance Festival each choreographer had five minutes on the big stage at Yerba Buena. Three programs. Thirty-five companies. An equitable and representational form of democracy that celebrates a utopian correction to the cultural segregation of most of our daily lives. This kind of democracy is also championed by the Izzies (the Bay Area’s Isadora Duncan Dance Awards) and might even be considered a San Francisco or Bay Area ‘Value.’...

ALMOST EVERYTHING I’VE EVER WANTED TO SAY ABOUT BAY AREA DANCE BUT DIDN’T HAVE THE CHANCE

Keith Hennessy responds to the 2008 WestWave Dance Festival

August 16-24, 2008

Produced by Dance Art, Dancers’ Group, YBCA

Dance Wave 1, 2, 3

The Novellus Theatre at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

Equality. Free Speech. Democracy’s Body. The Bay Area. The West Wave Dance Festival. In the future everyone will have 15 minutes of fame. In the West Wave Dance Festival each choreographer had five minutes on the big stage at Yerba Buena. Three programs. Thirty-five companies. An equitable and representational form of democracy that celebrates a utopian correction to the cultural segregation of most of our daily lives. This kind of democracy is also championed by the Izzies (the Bay Area’s Isadora Duncan Dance Awards) and might even be considered a San Francisco or Bay Area ‘Value.’

Diversity is generally a white liberal idea. Multicultural ensembles, as well as arts spaces and festivals that offer multicultural programming, serve an audience that is primarily white, i.e., not diverse. This held true for this year’s West Wave festival. If diversity programming does not attract diverse audiences, what is its goal? What aspects of the West Wave festival were not compelling to local audiences? With each company having only five minutes on stage, the reason to attend was not to see a specific company but to be wrapped in a crazy quilt of found fabrics, to taste test from an international smorgasbord, to enjoy or be challenged by juxtapositions, comparisons, frictions, and resonances between companies. From this holistic or systems view the 2009 West Wave Festival was a delightful success. But if so few people want to experience this wide-angle portrait and if the blackouts between pieces symbolize cultural divides that no amount of stage sharing can bridge then should this form be repeated?

The intentional creation of multicultural ensembles (SF Mime Troupe, The Dance Brigade, ODC) has its roots in a radical critique of mainstream society’s institutional racism. These troupes emerged from 1960’s and 70’s counter-cultural contexts inspired by the radical left, lesbian-feminism, and a series of ruptures in the arts. During the turbulent 60’s the established powers that refused to defend Native American independence or Civil Rights were quick to fund Alvin Ailey as the #1 American cultural export. An image of African American inclusion contrasted the facts at ground level. Progressive and reactionary forces are continuously at play and depending on one’s perspective social justice is improving (Obama) or not (US schools, prisons). The white choreographers and audiences of the SF Ballet receive massive and disproportionate funding from both public and private sources. Simultaneously, there are people in several powerful positions in Bay Area arts funding and presenting who are deeply committed to equitable distribution of resources and increased visibility for minority and/or marginalized cultures.

A review written in the spirit of the West Wave Festival would give an equal amount of commentary to each company that performed. It might even give each group the same quality of praise and/or critique, interrupting any attempt to favor or privilege one performance over another. My response is more subjective, as evidenced already by a particular politicizing of perspective. I am a fan of postmodern strategies and critical of dance that seems either nostalgic or unquestioning of tradition.

There was a striking similarity to most of the 35 dances staged in the festival. Dancers entered in the dark. The lights came on to reveal dancers in a still shape. Dancers moved in time to music for somewhere between four minutes, thirty seconds and five minutes. And then, in an obvious relation to music or narrative, the dance ended with stillness (or a repeating movement), and a slow fade to black. The audience applauded.

Interruptions to this structure were infrequent enough to stand out as nearly daring even if they simply used other accepted choreographic tactics, like walking on in light (Smith/Wymore), beginning in the audience and then moving to the stage (Chris Black), or dancing as if there was no beginning or end (Amy Lewis).

I have been looking for a way to simply describe Bay Area or American dance that seems to ignore most of the innovations and experimentation of the past 50 years, since Anna Halprin and Cage/Cunningham through Judson, performance art, contact improvisation and even Sara Shelton Mann/Contraband. (Disclosure: I performed with Contraband from 85-94.) European dance writer Helmut Ploebst uses the awkward term “modernistic American post-post-modern” to contrast Bill T Jones, Stephen Petronio, and Neil Greenberg from their contemporaries in Europe including Meg Stuart, Jan Fabre, Jerome Bel, or Vera Montero. I think his term could also apply to several contemporary Bay Area companies including ODC, Deborah Slater, Stephen Pelton, Brittany Brown Ceres, Janice Garrett, and Leyya Tawil. But of course this kind of classification is mostly useless and unnecessarily divisive. Kathleen Hermesdorf’s group choreographies might fit this term but her duet work with musician Albert Matthias does not. Alex Kelty’s choreographic research projects interrupt many modernist notions but his dance for Axis shown in West Wave was an expressionist dance-theatre drama that could easily be classified as post-post-modern.

I apologize in advance to the 35 choreographers whose work I mention here. I use your creative labors to spark an eclectic critical commentary on tendencies in Bay Area contemporary dance (and beyond). Certain prejudices prevent me from experiencing your work as you intended. Seeing the performance and reading the program bios demonstrates each and every choreographer’s deep commitment to dance. From a deep well of dance-making experience I respect the deep commitment, personal vision, and years of hard work with inadequate resources that is embodied in each of the following dances.

Given the massive effort it takes to accomodate 35 companies sharing a single stage, each program ran remarkably smoothly, production values were high, and everyone looked great in lights designed by Michael Oesch. Congratulations to the producers, technicians, designers and dancers.

Dance Wave 2

Wednesday August 20, 7pm

To a striking song of acapella voice and clapping by Quay, Alayna Stroud began the evening with a dance on and around a suspended vertical pole. Bold sharp arm gestures punctuated a dance of moody poses. With Quay singing of an inability to let go of the pain, the dance ended with Stroud, high on the pole, spinning, inverted, holding on.

An ex-SF Ballet dancer now award-winning international choreographer, Robert Sund offered a trio ballet to Leonard Cohen songs. Leaping and spinning, Ryan Camou generated an energy that was not met by his partners-en-pointe, Robin Cornwell and Olivia Ramsay. The choreography and performance seemed more like an earnest study for young dancers than a finished work appropriate to this scale of venue.

Ankle-belled and brightly dressed in orange and green, seven dancers from the Odissi dance company Guru Shradha performed a ritual dance of slowly spiraling arms in lovely light. The group formations, always frontal facing and symmetrical, seemed to freeze the action within the confines of the stage, rendering it a visual event to be viewed rather than a spiritual event to be felt.

A trio of women in white danced an impeccably synchronized choreography of glances and head gestures. Choreographed by Wan-Chao Chang whose extensive cross-cultural training includes Balinese dance and music, There was like something that Ruth St. Denis dreamed of making but lacked the technical training to manifest. The work recalled a women’s Modern dance chorus from the 1920’s or 30’s updated with deeply embodied non-Western movement that could only be possible with the cultural migrations and fusions of the past thirty years.

Cynthia Adams and Ken James of Fellow Travelers Performance Group choreographed an absurdist romp that satirized martini culture, an easy target. The central image was a dancer (super compelling Andrea Weber) attached at the back by a long wooden pole to an enormous wheel. It looked like it a design by Fritz Lang or Hugo Ball. As she muscled herself to spin, the wheel circled the stage while martini holding dancers ducked or swerved to avoid being knocked over. Dancers traded clothes, Ken ended up wearing a dress, and Cynthia crossed the stage with a vacuum. No one noticed the woman-machine that kept it all moving.

In this festival everyone gets five minutes. That’s one image, one gesture, one relationship, one moment within a twelve-scene event. In this context Christy Funsch made a clear and subtle choice. Alternating curvy sensual gestures and sharp punctuating lines, Funsch slowly traversed the stage. The music, like the dancing, was emotional but not dramatic. Reading her body’s writing from audience left to right, I was drawn into the choreography, and therefore the body, and thus an intimate encounter.

The most memorable sense I have of Deborah Slater’s Gone in 5 was the joyful meeting of full-bodied dancing (big leg circles, tumbling off tables), bluegrass with a driving beat, and untamed red hair. A female trio in red wigs and black dresses seemed to enjoy every bit of their five minutes but I missed the conceptual/intellectual engagement that inspires most of Slater’s dance theatre. By this point in the program I wondered if the five-minute rule and the late summer scheduling encouraged a lite touch, or discouraged more serious inquiry.

Innovators of the American Tribal style of belly dance, Carolena Nericcio and Fat Chance Belly Dance began with controlled undulations of arms, spine, pelvis, and belly. In super colorful costumes they gathered speed, energy, and volume, with finger cymbals rocking, into a final gesture of accelerated spinning, their skirts dancing like flames.

Amy Lewis’s Dada meets Judson happening was a delightful revelation. Titled and performed as a series of tasks, 35-40 performers filled the stage playing cards, wrapping gifts, stacking blocks, juggling, stuffing balloons in their clothes, and jumping rope. A trio of musicians played live. Two dancers in wheelchairs snaked through all the activities linking them like unraveling yarn. Someone read kid’s books. An actual kid did something else. Andrew Wass and Kelly Dalrymple, wearing their signature white shirts, red ties and black pants, repeatedly lifted each other from a chair at center stage. Others ran into the audience distributing free gifts. And that’s not all that happened! The stage came alive. The audience woke up. Reviewer Rachel Howard wanted to flee the theatre. People wanted to know what was going on. (What the heck was going on?!!) People wanted it to end. People wanted a gift. This is the piece that made it worthwhile for me to leave the house and risk my attention on dance. Thank you Amy.

Hip hop renaissance woman Micaya served up a celebration of booty that recognized its own hype and played the hip hop game with a self-awareness that the suckers on MTV can’t conceive. The choreography flirted with the music’s butt-worshipping lyrics, as if the body (booty) could talk back, call and response. Her diverse young crew, SoulForce, jumped through musical genres and even crumped to classical.

As soon as SoulForce arrived on stage, their friends (friends of hip hop) started calling out to the dancers in a kind of direct feedback that Rev. Cecil Williams referred to as “listening Black”. Dance styles are not the only ways that dance marks cultural difference. Audience response differs as well. Do we “listen Black” or “White”? Do we enter ritual spaces, times and trances or do we observe with fourth wall intact? And if we have a preferred style of response, is it appropriate to jump forms, or do we stay obedient and respectful of cultural norms? Some of us experience everything on the proscenium stage, from ballet to Afro-Peruvian, hip hop to performance art, as post-colonial and post-European. Are there any traditions that have escaped colonial conditioning? There is a difference between shared (diverse) and universal (we’re all the same). I wonder if by foregrounding the equitable sharing of space by diverse communities we exaggerate difference and emphasize borders, preventing the awareness of the universal fact that we all dance.

Kara Davis made one Tuesday afternoon… for a group of young ballet dancers from (I assume) the LINES ballet school. Eleven dancers moved from whole group movement to duets in which the dynamics of shared weight spoke to human connection and mutual influence. One falls and domino ripples of weight pass through the group. It’s easy to fall into the trap of treating young or student performers as the adults they want to become. Davis artfully avoids this trap by leading these ballet bodies into relaxed weight and playful encounters. As well the simple costumes of nearly monochrome brown street clothes helped a more innocent sensuality emerge. The minimalist bluegrass score by Gustavo Santaoalla well supported the piece.

Kumu Hula (hula teacher) Káwika Alfiche and several of his students performed A Goddess with live singing and drumming. The work began as a solo invocation within a circle of light. The fabulous costumes involved big full skirts and circles of what seemed to be dried grass or brush around their ankles, wrists and head. The headpieces were like organic halos, bursts of energy extending in all directions. The program notes inform that the dance tells a dramatic story of volcano goddess Pele’s youngest sister. The movement was mostly front facing and synchronized and I lacked experience to follow any gestural or energetic narrative. What I could sense was cultural pride through an attention to visual, sonic, and gestural craft.

In DanceWave 2 there were nearly as many people on stage (partly due to Amy Lewis’ cast) as there were in the audience (approx. 100). Why aren’t more audiences attracted to this programming? Is it so tough to convince friends or colleagues from particular (dance) communities to see you perform if you’re only on for five minutes and sharing the stage with eleven other companies that do not share the same music and dance culture? I think that if the tickets had been $5 or free with a request for donations, (instead of $25 with a $7 service charge), the producers could have doubled or tripled attendance with no loss in box office income. But that doesn’t answer the larger question about what compels people to attend or avoid contemporary dance performances in any style.

Dance Wave 3

Wednesday August 20, 9pm

Working in both San Francisco and European dance contexts causes some dissonance in my perception. In the Bay Area we accept overt religious practice in the form of folkloric songs and dances as a normal occurrence. In Europe this would be considered highly unusual, either ridiculed as naïve or witnessed from a non-believing distance. I have never experienced what we unfortunately call Ethnic Dance in a contemporary dance context in Europe unless the dance/music forms are in an experimental encounter with European forms, or the forms themselves are being questioned or deconstructed. Every time I refer to my work as ritual (and I do), a European brow gets wrinkled. Still I question the language of god and religion in our work, especially as we advance towards a presidential election in which every candidate feels compelled to end their speeches with an emphatic, “God bless America.”

Aguacero is a Bomba company directed by Shefali Shah. Focused on Afro Puerto Rican Bomba the company sincerely describes their work as connected to basic folk religion practices: healing, ancestor worship, embodying the natural world, and initiating youth in traditional practice. Their work is a syncretic encounter of West African cultures filtered through the Caribbean while reframing Spanish colonial dresses, shoes and language. At Dance Wave 3 they performed Hablando con Tambores a dynamic skirt waving dance that surfed the fast-paced, joyful wave created by three drummers and four vocalists. After a lively solo, a second woman came on stage in a competitive/collaborative face-off of tightly patterned skirt tossing, moving so quickly that my eye memory retained traces of circling and spiraling fabric.

Like her Ballet Afsaneh colleague Wan-Chao Chang (DanceWave 2), Tara Catherine Pandeya has cross-trained in several non-Western dance forms and traditions. In a dance of circling hands and micro percussive movements of shoulders and head, Pandeya danced in a sensual world evoked by the music played live by the trio Marajakhan. The traditional Uyghur music and the long braids attached to Pandeya’s hat recalled the work of Ilkolm Theater (Uzbekistan) who performed the gorgeous epic Dance of the Pomegranates at Yerba Buena earlier this year. Both performances evolve from diasporic Central Asian Turkic cultures.

Alex Ketley in collaboration with Rodney Bell and Sonsherée Giles of Axis Dance Company created a tense and intimate dance drama. Punctuated by quick gestures and sudden conflict the lovers seemed caught between intense attraction and secret fears. The dancers’ intimacy with each other’s bodies further demonstrated the struggle of any two people to connect. In this case the two people had to cross the divide between man and woman, as well as between a person who walks on feet and legs and another who travels by wheelchair. When Bell fell backwards to the floor, supported by Giles, we realized that he was fully strapped to his chair and could now crawl like a snail with house attached until he muscled his way upright. The piece ended the way it began and why not? Most couple encounters circle through familiar territory.

Brittany Brown Ceres choreographed Shade a quintet of women bound in a space defined by a rectangle of light. The work alternated synchronized and solo movement with a variety of lifts to a score of uninspired contemporary techno. An unfair question blocks my vision. “Why are they dancing like that, working so hard with such tired vocabulary and choreographic assumptions?” This question only reveals my inarticulate frustration. Also it seems too specific about dance ceres (whose work I’ve never seen before) when in fact I ask it all the time when seeing post postmodern Bay Area dance. In the program text Ceres tells us that Shade was “crafted in public spaces to study landscapes which are designed to substitute for psychological balance and to unlock descriptive communication made of movement instead of words.” The gap between their craft and my experience was overwhelming.

The strangest work in the West Wave Fest was Brooke Broussard’s Moving The Dark. A solitary figure in black unitard, complete with hood, moved continuously in rhythmic patterns of extended sweeping limbs and undulating spine. In some contexts this costume and this action would cause uproarious laughter but here it was only weird, as in otherworldly. Three lengths of blue carpet were unrolled to mark the space into a geometry of lines and triangles but the choreography seemed to ignore these differentiated spaces, so after a couple of minutes I did the same. Six other dancers in three pairs completed the cast of this surreal-psychological modern ballet. Blackout. We clap. Then we hear a loud scream.

A woman’s voice is heard from the balcony. Some pop song I can’t name. “I’m gonna make a change in my life.” Then singing erupts throughout the well-lit house. The singing, by choreographer Chris Black and company, was charming as if we caught these citizens singing along with headphones on a rural trail or alone in their apartment. Moving towards the stage one of the performers faces the audience from the front row and sings only the first half of U2’s “And I still haven’t found (what I’m looking for).” A repeating motif of “change” of course recalls Obama but it is only afterwards that I find out that the piece is entitled Headlines and includes found gestures from print media with a fractured medley of pop music. Musical encounters between the performers grew increasingly complex, mashing one song against another, or everyone briefly singing the same song. Counting aloud, Michael Jackson’s Man in the Mirror, and little dances of borrowed shapes in absurdly out of context scenarios, became a virtuosic arrangement and performance of everyday life. The emotional power of this piece was a surprise. What seemed like a formal intervention and a cute referencing of pop culture became an impassioned cry for renewed meaning and solidarity. Wow.

Tango Con*Fusion offered a round robin of tango duets danced by an ensemble of six women betraying (they call it bending) the gender roles of traditional tango. Bay Area values have evolved to a point where bending gender and queering tradition is neither radical nor compelling. The dancing seemed polite, lacking the intimacy and tension that tango often evokes. I was reminded of Terry Sendgraff’s aerial dance company in the 80’s embodying a (lesbian) aesthetic that avoided competition and celebrated equal partnership. You might need to check your punk rock at the door to be able to enter the best of these egalitarian worlds.

Through Another Lens by Sue Li Jue is a modern ballet that confronts the legacy of the Vietnam War within a body that is both American and Vietnamese. The sound score succeeded in blending two distinct voices: a blues text by an American vet underscored by traditional Vietnamese folk music. Soloist Nahn Ho is a strong dancer whose spiral falls, clear shapes, and sudden turn to the audience dared us to witness him, a young man pushed to the limit by the political tensions that he embodies.

Second generation South Indian dancer and choreographer Rasika Kumar crafted the festival’s most overtly political piece. Gandhari’s Lament represented the story of the blind mother of 100 sons who were all killed in the Great War of the Mahabharata. With ankle bells marking every percussive step, Kumar’s powerful dancing used both abstract and mimetic movement to communicate a mother’s grief. Her bitter, closing curse could as easily be directed at today’s murderers.

Zooz Dance Company’s En Route opened with a gorgeous solo by Jessica Swanson in a backless top that highlighted her amazingly articulate back and hips. The fusion dancing of Zooz, co-choreographed by Jessica McKee, features ensemble Middle Eastern dance that is super precise and seductive. Their skirts, especially the boa-like trim, did not meet the quality of the dancing.

If an internal voice demanding “Why? Why?” prevents me from seeing most Modern dance made by contemporary choreographers, the volume elevates to near screaming when I’m watching modern ballet. Liss Fain’s Looking, Looking was another of the festival pieces that seemed like a study for young ballet students. How did these works get curated over the sixty choreographers who got turned down? Was there a category for student works? Or did these pieces represent the best of the ballet applications? In Fain’s work two men and five women in sexy black shorty shorts danced for five minutes to Bartok’s dramatic Concerto for Viola. There were lifts and arabesques; the dancing was neither stupid nor compelling.

Dance Wave 1

Thursday August 21, 9pm

Charlotte Moraga restaged and performed an original composition by Kathak icon Pandit Chitresh Das. The dance basically manifested its title, Auspicious Invocation. With liquid wrists, crystalline forms and an open expressive face, Moraga began in a circle of light, dancing her invocation to the four corners. Properly concluding the ritual, she ends with a bow. Moraga is an excellent dancer who has been immersed in this form for 17 years.

But what does it mean to wear a sari or Indian costume on stage in San Francisco? What relevance or resonance does a contemporary audience appreciate when watching traditional ritual dances? What combination of training and inspiration might result in a local Akram Khan? Someone who masters Kathak and subjects it to contemporary and global questions of performance? Someone who no longer feels responsible to represent a nostalgic or idealized cultural representation? Similarly what social context might encourage an African American dancer in the Bay Area to dare the kind of genre-busting performance of Faustin Linyekula? Someone whose expression of African-ness is dependent neither on folkloric tradition (pre or post slavery) nor on the specifics of urban Black cultures? I wonder what might happen if some of the local ‘ethnic’ companies abandoned representational music, costumes, and static ritual forms. I have been inspired by the complicated revelations of Khan, Linyekula, and other companies directed by non-Western artists traversing the borders of genre, ethnicity and culture, reframing ritual and spectacle for today.

Recent Bay Area resident Erika Tsimbrovsky crafted an evocative teaser of visual dance theatre that suggested we keep an eye towards further projects. Paper gowns that ballooned around the dancers as they dropped suddenly and a scratchy recording of a slow turning music box evolved a performance language sourced in image and memory. The dancers hid inside the dream space of their skirts, and two of them birthed themselves naked as the lights faded.

Sheldon B. Smith and Lisa Wymore made a smart, hip little dance generated from YouTube. Imitation, lip-synching, and multiplying the action via ensemble movement heightened our attention to the found sources and challenged a reconsideration of live performance’s relationship to online videos. What does it mean when highly trained dancers are viewed by an audience of 100 or 200 when non-professionals can be viewed by 3 million? Not only is YouTube a bigger performance archive than we could ever have imagined, but nearly all of YouTube’s most viewed videos involve dance or bodies in performance. Too many of the Dance Wave artists entered in the dark and held a static pose as the lights came up, so it was an unintentional and pleasant intervention to have the Smith/Wymore quartet walk onto the stage with the lights on.

In Mary Sano’s Dance of the Flower a woman’s head floats above a massive parachute skirt, under which we assume many dancers are hidden. To Bach’s cello the skirt begins to breath. I’m in a retro shock. Really retro. I’m thinking Duncan, perhaps after Fuller. This is neither an innovative skirt dance like Fuller’s nor a well-researched prop piece that recalls Mummenschanz or Momix. It’s more like a children’s theatre game evolved from metaphoric, expressive early Modern dance. Emerging from the skirt we are presented with a lovely poem of skipping women in Duncan-style, Greek-inspired tunics. (How many companies in this festival are all-women?) Sano, a third-generation Isadora Duncan dancer, choreographs under the influence of a series of assumptions about nature, women, dance, bodies, and flowing fabric without any recognition of the nearly 100 years of challenging and rewriting those assumptions.

Most Bay Area dancers work with such a poverty of resources (money, space, time, scheduling, management) that it is a marvel that there were nearly 100 companies applying to be in this festival. Nonetheless the lack of engagement and risk with visual design, especially light and sets, is often disappointing. This is as true for the last ODC concert that I attended as it is for most of these five-minute wonders. Dandelion’s Oust (excerpts) began with an odd solo backlit by an upstage performer with a handheld instrument, while a woman at a microphone laughed. The light shifts to another dancer who writhes, falls, twitches and freezes. Unfortunately this is neither Eric Kuyper’s strongest work with the company nor a great example of why we ought to experiment with light. But Kuyper continues to intervene with tradition, challenge conventional assumptions, and craft risky interdisciplinary experiments.

Smuin Company resident choreographer Amy Seiwert created Air a ballet pas de deux featuring Jay Goodlett and Tricia Sundeck. These dancers have considerable professional experience compared to the ballet dancers in Programs 2 and 3 which made this dance all the more disappointing with its lack of risk and insistence on neoclassical vocabulary and stale gender roles. The crowd was loud and vocal with praise. SF Chron reviewer Rachel Howard thought it was the best of the fest. I’m sure that Goodlett is a fabulous dancer but at Trannyshack, SF’s legendary drag club, he would be referred to as a ‘man prop’ (the male as functional object in service of the “female”). In diva culture this is not necessarily an insult.

Charya Burt’s Blue Roses reimagines Laura from The Glass Menagerie as a Khmer princess trapped in her own world. Wearing traditional Cambodian clothes Burt knelt in a circle of light, her wrists held at a sharp 90 degrees, palms pushing out, her fingers reaching well beyond their physical length. Despite the specific cultural invocation of gesture, costume, music and light projection Burt avoided mimetic acting in favor of detailed and articulate physical expression. Her intense presence and sensitivity were so palpable that even the subtlest of wrist and head movements seemed to charge the space around her. Similar to the slow intensity of early Butoh or Deborah Hay’s cellular movement the audience could either be bored to sleep or provoked into a radical encounter with the present, presence. I was impressed, touched.

Nine bodies in white, on their backs, marking the diagonal. In waves of canon the dancers of Loose Change pulse into and up from the floor. Choreographer Eric Fenn’s vocabulary reveals itself slowly in fragmented reference to break dance, hip hop and more. Percussion-based group movement proves this crew is the strongest large ensemble of the festival. Invoking a future city of dance monks the team falls into place remaking the opening image.

Another transition between companies. Another attempt at discreet set up in soft blue light followed by a black out, followed by lights up on dancers in stillness. Would it hurt to reveal the action, skipping the blackout and the precious stillness? Does the stage have to remain this nostalgic place of magic? How did the dancers get there? I don’t know they just appeared in gorgeous light and then started dancing.

I’m curious to see more work by Limbinal a young collective of artists directed by Leonie Gauthier. For their five minutes they presented INside which featured two man/woman duets, one on a table, accompanied by live cello. The work on the table, the mutual lifting, and the increasingly dramatic cello suggested a meeting of Scott Wells and Sara Shelton Mann in a chamber ballet.

Women lifting men ought to be more common in 2008 but its only other occurrence in this festival was with Wass & Dalrymple in How many presents… Contact Improvisation began in 1972 with an intention to democratize (remove the hierarchies from) the duet. But this is only one of the aspects of the postmodern dance ruptures that seem generally absent in Bay Area contemporary dance.

Luis Valverde (choreographer) and Eleana Coll gave a rousing presentation of Peruvian Andean dance. She, fabulosa in pink satin and white ruffles. He, dapper in blue suit, black boots, woven belt and wide brimmed white hat. Hankies revealed in their right hands, they begin to court each other. Indigenous footwork in colonial drag, they dance a timeless seduction of approaches, smiles, spins, and retreats. Their steps are rhythmic and light. The music alternates between symphonic and a military snare. These are handsome people and we want them to get together. When their faces pause almost touching, almost kissing, I want to cheer. The steps increase to skips but she never loses her coy cool. Now the hips are marking time more than the feet. A big energetic finale, racing against the music and they freeze, together. Big applause.

A voiceover instructs us to turn on our cell phones and invites us to document the dance. On stage are two men and one bride. The audience starts snapping pics. And thus begins Snap a work by Jenny McAllister for Huckaby McAllister Dance. A long tulle train attached to one man, when pulled, drags three pink dressed ladies onto the stage. The voice clowns our habit-obsessions with phones and the documentation of every waking moment. “Keep the truth safe from time. Isn’t that beautiful?” For a while this is physical comedy via ensemble dancing. Then the voice talks about grandparents in Minsk and the only photo in which no one smiled. “Bubby says it was just like that.” With efficient craft the weight of history is invoked and the simple social satire becomes only a preparation for a more intimate touch to occur.

Somei Yoshino Taiko Ensemble closed the evening with a fusion performance in which the dancers were the musicians, and the dance was an enactment and embellishment of the musical score. Four drummer/dancers moved around and within a circle of large and small drums. Sharp strikes from one arm. Boom! The other arm shoots vertically to the sky, extending its line with drumstick in hand. Quick shift. Boom! The energy ebbs and flows in a continual flirting of yin and yang carrying marked by stark freezes and silences. Synchronized activity amplifies the sound in such a concrete way: more drummers, more force, more sound. The pace increases towards a quick finale. The final gesture’s silence is the loudest action of it all. And they drop, disappearing into the center of the drums.

In a film clip shown at the Nijinsky Awards in Monaco a French interviewer asks, “WHAT IS dance to you, Mr. Balanchine?" The response was, "just dance."

Jess Curtis / Gravity • Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

The stage is filled with the remnants of past performances, stuff that seems to have lost either its meaning or function. Objects from theater prop rooms: mannequin parts, black cubes, an old fridge, a child’s desk, a vintage gurney, a bike, a mirror, and even the kitchen sink, ba da ba. This is the trash of representation, stuff that looks like or evokes or locates… The appearance of the sink suggests a hint of vaudeville, that US American entertainment fusion of dance, comedy, circus, sideshow, and cultural performance...

Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

(Preview excerpt)

Jess Curtis / Gravity

February 28, 2010

Presented at CounterPULSE (San Francisco) as part of Gravity’s Intercontinental Collaborations 4.

Created & performed by Maria Francesca Scaroni, Jörg Müller, Claire Cunningham, David Toole, Jess Curtis and dramaturg/provocateur Guillermo Gomez Peña. Conceived and directed by Jess Curtis.

The stage is filled with the remnants of past performances, stuff that seems to have lost either its meaning or function. Objects from theater prop rooms: mannequin parts, black cubes, an old fridge, a child’s desk, a vintage gurney, a bike, a mirror, and even the kitchen sink, ba da ba. This is the trash of representation, stuff that looks like or evokes or locates… The appearance of the sink suggests a hint of vaudeville, that US American entertainment fusion of dance, comedy, circus, sideshow, and cultural performance.

Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies

includes all of these elements, but under the influence of contemporary dance and performance these elements are either reduced to abstract essence or maximized into camp excess. The mashup of these tendencies - towards essence or excess - defines the field of play for this team of improvisers.

By referring to the bodies as Non/Fictional, Curtis emphasizes the impossibility of denying the fiction within nonfiction, the imaginary within the real. The slash that interrupts the more commonly used ‘nonfiction’ intervenes on a simple reading of nonfictional as non-imaginary, not-pretend. The bodies in this carefully constructed mess recycle and repurpose objects as easily as personae, changing costumes and attitudes, wigs and positions. In Dances for… the body is real is a theatrical construction is a performance is an unstable and generative site of production of identities, knowledge and art. Dancers sing, juggle, ride bikes, imitate circus animals, manipulate objects, and dance. Sometimes they do almost nothing, daring us to stare or to question what is real. In their playful experimentation bodies and bodily talents are revealed as well as hidden. Two of the five performers have bodies that might be described as disabled, differently abled, non-normative, crippled or different. Everyone has a crutch, that is, a way of extending themselves with objects, tools, or other people to achieve things they wouldn’t be able to do otherwise. These humans seem broken yet undefeated. Together they build a queer world beyond the obvious, the norm, the rule.

The choreography or dramaturgy of this splendid provocation in the guise of a theatrical performance is not obvious. It’s more like a gestalt of performative actions, images and interventions. For most of the work there are multiple simultaneous events. A crisis of representation, of identity, is provoked by this crisis of choreography. The dancers demonstrate both virtuosity and banality. The five performers work alone, in duets and trios. Neither my notes nor memory of this densely layered performance recall any moment when all five were in the same game or image. The following descriptions attempt to resist a falsely linear chronology of the chaos-like multiplicity, simultaneity, and confusions that structure (and de-structure) the work.

Claire enters, most of her body and head covered in some kind of over-sized, insulated welding suit. In her gloved hands she holds crutches like enormous tweezers carrying a plush bunny, as if it is toxic and must be kept away from everyone. Funny. Strange. Then I notice the only parts of her body that are visible: ankles and feet. Her feet are oddly flat and her ankles seem to dislocate or relocate with each step. Her walk is fragile and I realize that I’ve never before seen her walk without the aid of crutches.

In her body-distorting fat suit Maria swerves madly on roller skates, narrowly missing people, objects, and wiping out. At a blackboard she writes, “He hides in exposure. Love is a structure. I respect Spinoza. Me too. OMG.” Standing (in roller skates) on a table, Scaroni alternately sings and lipsynchs a song that includes the lyrics, “Only in my dreams.” Her camp entertainment is unexpectedly intimate. Maria’s skates prevent any stable position, keeping her always poised at the edge of danger or momentum. Later she returns to the blackboard, now naked, to write, “What scars you? How do you pretend to be strong? Did you sabotage my roller skate?”

After an (amateur) strip to underwear, Jörg appears in a red riding hood cape. Suddenly he jumps into a wide stance with bent knees. The cape opens to reveal a fuzzy pink bunny slipper covering his genitals. Legless David Toole’s muscular upper body seems to collapse into itself, diminishing his non-chair height to below Müller’s crotch. David reaches with his rubber-gloved hand to pet the bunny codpiece. As he continues to stroke the bunny, Jörg slaps his hand away. Bad boy! We laugh and squirm. The interaction is so queer, so peculiar, so gay, complicated and delighted by reading these guys as hetero dudes engaged somehow innocently in a contradiction of queer fetishes, rubber and plushy. Touch. Don’t touch.

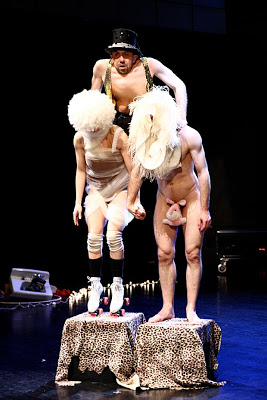

I nearly jumped to my feet to applaud the sublime circus-like act in which David plays both trainer and animal. He is wearing top hat and vest, and something animal print. The music is spaghetti western. Walking on his huge hands and powerful arms, David arrives on each block as if we should applaud. Ta da! See the trained cripple, I mean dancer, I mean freak, approach the wary audience. See how he balances and never falls. Maria and Jörg enter on hands and knees. Big cats. David commands them, pets them, and begins to climb onto their bodies. Slowly they rise, until they are standing (Scaroni still in roller skates!) on the blocks. Toole has continued to climb, to balance, until he is perched above their heads, his hands on their shoulders. Extraordinary. Bizarre. Edgy. Is the image more dangerous or unstable than the physical feat? The descent is controlled, awkward, and precise. In a hug, Maria carries David, and she skates them off stage.

In

Dances for…

Jess stages his most frequent practices: reading books for grad school and endurance bike riding. During a period of 15 or 20 minutes Curtis, geeked out in full lycra bike wear, rides a fancy road bike that powers a string of lights. He rides and rides. The action is vigorous. The impact almost ridiculous. He goes nowhere. The lights are meager. But his energy builds with the work, the sound of his labors increase via breath and spinning back wheel. With this increasingly intense action Curtis anchors the project.

Curtis, Gómez-Peña, and the collaborative performers have crowded this work with obsessions, desires, fears, taboos, fetishes, and archetypes. They’re playing with objects, playing with themselves and each other, playing with us, playing with ideas and representations, playing with identity, playing with bodies, playing with the con/fusion of real and imaginary. This serious and disciplined play informs a wisely crafted choreography of improvisations, situations, and sensations. The work is intended as provocation but does not shy away from entertainment. In the friction between contradictions Curtis and gang have generated significant warmth, raising the social temperature, daring us to playfully disrupt our own bodily fictions.

Kirk Read performance at Too Much! (Jan 2010)

Chicken Shit (meditation is supposed to make you less crazy)

Performance by Kirk Read

Kirk Read walked on stage carrying two milk crates. He was wearing a short white shirt-dress or choir robe that read ceremonial. The robe was closed at the throat but open to the torso, revealing gold lame bikini pants. A voice over of Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield’s trance inducing monotone introduced us to some kind of meditation practice. A wall-sized video projection of someone, someone white, touched and then later licked a small brown-skinned doll. The effect of the close-up fondling was creepy but almost camp, especially in contrast with what we hear...

Chicken Shit (meditation is supposed to make you less crazy)

Performance by Kirk Read

Kirk Read walked on stage carrying two milk crates. He was wearing a short white shirt-dress or choir robe that read ceremonial. The robe was closed at the throat but open to the torso, revealing gold lame bikini pants. A voice over of Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield’s trance inducing monotone introduced us to some kind of meditation practice. A wall-sized video projection of someone, someone white, touched and then later licked a small brown-skinned doll. The effect of the close-up fondling was creepy but almost camp, especially in contrast with what we hear.

Kirk stood on the two crates and attached a carabiner to a cord extending from the ceiling, lengthening its reach to approximately 3 feet above the floor. A (frozen) chicken on a silver platter was passed through the audience. Kirk received the chicken, which had been prepared with some kind of wire harness, and suspended it from the cord.

The voice over and projection continued. Kirk’s mood was calm as he moved slowly and methodically to set the stage. Some of us knew what was going to happen, but we knew that not everyone knew. The audience mood was unsettled, caught between images (real and imagined) that were both ominous and absurd.

Kirk moved the crates, with platter on top, away from the chicken. He turned his back to us and flipped the robe over his head, revealing his back. He pulled his pants down, and backed up, straddling the crate, which was positioned diagonally between his legs. He leaned forward, reached back, pulled his butt cheeks wide. The audience started to squirm, giggle, moan, recoil, chat. The first sign of shit elicited both gasp and light applause. The applause returned louder when the first turd was pinched off and dropped to the plate. Then he pooped a bunch more. Some walked out. Some applauded. The rest of us tingled, stared, squirmed, squeezed our neighbor’s hand or thigh, commented, took pictures with cell phones, laughed.

Just getting to watch an asshole open and release, for most of the audience, was a once in a lifetime event. Read crafted the event in a fresh hybrid of shamanistic body art vaudeville that somehow made the taboo acceptable, watchable, even interesting. Read’s onstage pooping was simultaneously funny, magical, and formally precise. How did he do it? I can’t believe he’s doing it! I can’t believe I’m watching this! Wow, look how much is coming out.

Then it stopped. He pulled up his pants (without wiping), fixed his robe, and turned around. He brought the crates, with platter of shit, back to the chicken. As if performing a demonstration in home ec class, Read dressed and stuffed the chicken. He dressed it with a skirt of streamers and stuffed it with spoonfuls of his own poop. He took his time, making sure not to waste any.

Then he moved the crates out of the way, looked up at us and smiled. The smile was coy, suggesting possible danger, but we didn’t have time to imagine what he might do next. When he pushed the chicken towards the audience, it swung over the first row and folks jumped out of their seats to get out of the way. Swinging it more erratically, to challenge even more of the audience, we laughed and squealed and more folks scurried out of the way. Some took their chances and remained seated, ducking their heads as the poop-stuffed chicken came their way. The shock was tempered with the ridiculous.

Before the chicken swing had come to rest, Kirk stopped it with two hands. He unhooked it and placed it in one of the crates. There was intermittent applause as Read reached up to detach the carabiner and gathered his props. He returned to the unhurried state of executing simple tasks, closing the ritual as he had opened it.

Read walked out. The applause was strong. He left no visual trace but the smell now seemed overpowering. The door to the small theater was opened, several people left and the rest were engaged in animated chatter, while fanning their hands in front of their noses.

I questioned the video and wondered what would be gained or lost without it. I adored the creepy vibe and the licking shots were really strong - I mean evocative, suggestive, inappropriate - but what did the video bring to the larger gestalt of the work? It introduced a juxtaposition or tension with the live performance that wasn’t sustained. Insufficiently developed video projection is too frequent an occurrence in dance and live performance.

In brief discussion with Read I know that this work was inspired by both a meditation retreat and a book about the horrors of factory farmed chicken. These diverse sources both crack the denial of how we’ll eat shit – real and metaphoric - as long as we don’t know what we’re eating. Read’s Chicken Shit (meditation is supposed to make you less crazy) is a provocative yet nuanced meditation. It will be notorious as a poop performance, but the complex resonance of the work ripples in ever-widening concentric rings to disturb the social surfaces of our denial.

Chicken Shit was one of over 30 performances at

Too Much! a marathon of queered performance

Mama Calizo’s Voice Factory, Jan 10 2010

Produced by Zero Performance as part of Keith Hennessy’s A Queer 20th Anniversary

Passing Strange (The Musical / Film)

Passing Strange

A movie by Spike Lee documenting Passing Strange, a Broadway musical with lyrics and book by Stew and music and orchestrations by Stew and Heidi Rodewald.

Before my brief comments on this concert/play/movie, here’s the synopsis from wiki:

“A young black musician travels on a picaresque journey to rebel against his mother and his upbringing in a church-going, middle-class, late 1970s South Central Los Angeles neighborhood in order to find "the real". He finds new experiences in promiscuous Amsterdam, with its easy access to drugs and sex, and in artistic, chaotic, political Berlin, where he struggles with ethics and integrity when he misrepresents his background as (ghetto) poor to get ahead...

Passing Strange

A movie by Spike Lee documenting Passing Strange, a Broadway musical with lyrics and book by Stew and music and orchestrations by Stew and Heidi Rodewald.

Before my brief comments on this concert/play/movie, here’s the synopsis from wiki:

“A young black musician travels on a picaresque journey to rebel against his mother and his upbringing in a church-going, middle-class, late 1970s South Central Los Angeles neighborhood in order to find "the real". He finds new experiences in promiscuous Amsterdam, with its easy access to drugs and sex, and in artistic, chaotic, political Berlin, where he struggles with ethics and integrity when he misrepresents his background as (ghetto) poor to get ahead. Along with his "passing" from place to place and from lover to lover, the young musician moves through a number of musical styles from a background of gospel to punk, and then blues, jazz, and rock. He finally returns home.”

This is a fab film that really loves the theatre it archives forever. I laughed a lot and was just wowed by so much of the writing. I was also impressed by the staging of drugs, anti-capitalist politics and performance art, that even when sarcastic and demeaning (typical framing in mainstream or big budget contexts), was also playfully right on and potentially subversive. The many references to Passing were super bright, insightful, playful, and satisfying. Energetically, the film suggests a performance that really moved its audience. Lee’s gorgeous close-ups provoke visceral and emotional response. The dramaturgy of energy, of rising and calming vibrant presences, might actually be the strongest element in this production.

I'm kinda surprised that Passing Strange was never on my radar - not that I ever track Broadway (or even Berkeley Rep where it was developed) but I usually know about performances of any kind that are so full of issues I care about. But maybe because the project itself passes strangely. It passes as different or experimental with regards to Broadway but then seems to recuperate Broadway’s ideological standards of promoting universals and (white) social norms. I say passes strangely because it is never quite what it says it is. It’s complicated. Which might be related to saying, it’s a Black middle-class thing, a performance of multiplicity, paradox and shifting position.

When the writing is not sharp and wonderful, it's too cliché and dumbed-down. Stew, the writer/narrator/star, knows all the reasons not to reproduce a sucky Broadway show and then he tries to do it. I mean sure it’s a personal narrative and maybe it’s even a True Story. But does a play smart enough to acknowledge feminism have to make every shift in a boy’s life be dependent on mom or girlfriend?

Did the writers and producers think that the only way to stage a non-Broadway song on Broadway is by quotation? The influences of punk, funk, minimalism, and performance art have been integrated into mass media and Broadway performance for years. In Passing Strange, the default is show tune ballad. Only when part of a play within play, the punks in Berlin for example, can we experience ‘alternative’ musical stylings. This default setting wouldn’t bother me so much if it was just aesthetic, but it is also ideological. Not just one drug scene, but pot, acid and speed are all instrumental to his artistic/political formation. But shit, is all the countercultural experimentation simply a distraction from the reals (ideals?) of family, christmas, and musical theatre? This default to normative family somehow can’t recognize that the ways we construct family are central to the lead character’s struggles with identity and authenticity, with finding what’s real. What's next - a thanksgiving musical where a gaggle of freaks gather to un-ironically feast on turkey with a 'medicine day' chaser? (Sorry if that reference is opaque. There are 100 people who know exactly what I’m talking about.) Anyway, help me out as I stumble in this slippage between hi and low, downtown and midtown, rich and poor theatre. I feel duped.

PS.

I would like, at least once in my life to have one of my own performances documented so well.

PPS.

Duped means deceived and the word originates form 17th cent dialect French about some bird whose appearance was supposedly stupid.

Scott Wells & Dancers, Men Want To Dance

What Men Want

Scott Wells & Dancers

May 31, 2009

Part of the 2009 SF International Arts Festival

ounterPULSE, SF

Scott Wells makes wonderful dances for men and women and sometimes he makes wonderful dances for men. Wells treats modern dance like a sport in a postmodern fusion of relaxed lyrical dancing, physical comedy, and surprisingly tender partner acrobatics. The leaps, catches, cat like landings and spiraling falls to the floor reveal the company’s roots in the dance known as contact improvisation...

What Men Want

Scott Wells & Dancers

May 31, 2009

Part of the 2009 SF International Arts Festival

CounterPULSE, SF

Scott Wells makes wonderful dances for men and women and sometimes he makes wonderful dances for men. Wells treats modern dance like a sport in a postmodern fusion of relaxed lyrical dancing, physical comedy, and surprisingly tender partner acrobatics. The leaps, catches, cat like landings and spiraling falls to the floor reveal the company’s roots in the dance known as contact improvisation.

What Men Want was a suite of four premieres, including two big works for an ensemble of eight men. In this meandering writing, I don’t review each piece. I’m exploring a few ideas, mostly about men dancing.

Wells’ work for men charms with a playful engagement of masculine clichés, anxieties and interventions. The work is so unabashedly straight, as in heterosexual, that it’s almost queer. I mean that Wells and his guys, regardless of their personal identities and affections, come across as straight dudes whose physical intimacy most often recalls the homosociality (aka male bonding) of a compulsively hetero locker room. At other moments of sensitive dancing and careful touch the choreography dares to intervene on hetero norms. We don’t expect sporty dudes to roll together quite so slowly. It’s queer in it’s intentional questioning of masculine performance. If there’s a weakness to this expansive view of hetero masculinity it’s the way that Wells’ choreography responds to nearly every gentle moment with a kind of defensive reaction of physical comedy, martial arts jokes, or just vigorous muscular activity. The choreographic rhythm is like a pendulum that inscribes a binary code, swinging from masculine to feminine, gentle to vigorous, sensitive to hilarious. This binary insistence is decidedly not-queer. The only device I contest is the ubiquitous ‘gay joke.’ There are a million variations - in dance, television, sports, Hollywood, advertising – in which two or more guys suddenly become aware of how intimate they’ve become, and the energy shifts, and the audience laughs. And that laugh, for queer boys, is too often a cruel laugh.

K. Ruby was a dance student and choreographer at Berkeley High 30 years ago. Recently, she told Linda Carr, the current head of Berkeley High’s dance program, how times had changed. With the addition of hiphop to the dance curriculum, it seemed to Ruby that more boys were dancing. She recalled that classes in the late 70s were predominantly female except for the occasional gay or soon-to-be-gay male. Carr pointed out that, sadly, today’s gender demographics were consistent with Ruby’s experience. And that’s the news in a town noted for its liberal and radical social politics, in a Bay Area known worldwide as a place for queer challenges to normative behavior. How much does gay anxiety and homophobia influence our dance cultures? Why is it so unusual for men to dance together in this culture we might call contemporary or post-European or even post-colonial? In Ballet, Modern dance, and the styles that follow, females are probably 80% of the practitioners, many in training since the age of four or five. Males start dancing later, take fewer classes, have significantly less competition for professional opportunities and consistently get more attention and resources. Despite the male dance superstars from Nijinsky to the Nicholas brothers, from Gene Kelly to Baryshnikov, and from Jose Limon to Savion Glover, dance – in the American popular imagination - continues to be gendered female, or feminine. Try to consider this while simultaneously and paradoxically noting that the most viewed YouTube video (100 million + hits) is a comic dance by Jud Laipley called The Evolution of Dance, AND the top prize for the past two years of Britain’s Got Talent was won by male dancers, who received millions of votes and even more YouTube hits. Diversity, a multi-racial, age diverse, all-male dance company, won this year’s prize and the 2008 winner was a 14 year old named George Sampson who performed a hiphop remix of Kelly’s Singing in the Rain. European and American boys and men are dancing but they’re still not taking modern dance classes in any great numbers. Scott Wells & Dancers operates within this larger social context of homophobic masculinity, gendered dance expectations, and special attention for dancing boys.

The two jewels of this oddly named evening of dancing were the smaller more formal works, Catch, a duet for two dancing jugglers, and Bach solo trio, danced by a solo woman and a trio of guys. I think I like Catch because of the lack of comedy. The duet connection between Aaron Jessup and Zack Bernstein (of Capacitor) was super sweet. All dance duets are about love, but some are less romantic than others. In this pas de deux with objects, the love was a shared loved. If I could call it Whitmanesque and not evoke sex, I’d call it the (chaste) love of comrades. They danced on and around each other’s bodies, always a red ball in hand, or traveling between them. As the work progressed, virtuosic ball tossing alternated with swirling lifts and spiral rolls over backs. Sometimes there was one red ball between them, but towards the end they each juggled five balls simultaneously, beginning and ending in perfect synch. Impressive. The dance ended the way it began, roles reversed, one man a landscape of body lying in a circle of light and the other walking the perimeter.

Bach solo trio opened with a short solo by Rosemary Hannon. Hannon (recently seen dancing with Non Fiction at The Garage) repeated a short phrase focused on the arms and torso. Hannon is tall, lean and articulate, a hyper-aware dancer whose long arms unfold in delicious detail to the ends of her fingers. Dancing in silence, her breath had a resonant presence. As she exited, the Bach began, and the men, Andrew Ward, Sebastian Grubb, and Cameron Growden, entered. As they repeated the same phrase as Hannon, I looked for difference and tried to determine which details were because of gender and which were due to the particularities of these bodies. The men were each and all more compact and dense than Hannon. They didn’t have the openness of shoulder flexibility nor the articulate detail in their fingers. Unlike Hannon, they hadn’t been taking dance class since early childhood. The openness and breath in their chests felt like a distant reminder of Hannon. The men really came to life in the curvy tumbling and floating handstands. There was a section of low spinning into and up from the ground, weight on and off of hands, that recalled the Brazilian dance/fight form capoiera. When they spun on one leg and dove to the floor I recognized the influence of Wells’ body or the Scott Wells that I remember from ten or fifteen years ago. Grubb especially reminded me of Wells’ unique style. The trio section ended with a marvelous thrill of lifts and tumbles, every landing unexpectedly quiet, like cats. Hannon returned, with arms and fingers so alive, her curly mane extending every action of head and spine, and somehow it was her female-ness in response to the trio’s male-ness that filled the space, and took this piece home.

The eight men in the ensemble make a delightful team. In addition to the five men previously mentioned, there is Rajendra Serber, Cason MacBride, and Ryder Darcy. The guys are generous with each other, authentically affectionate, and trustworthy in their attention and precision. Their joy of dancing is infectious and they love to entertain. Wells’ and his dancers are not hesitant to put on a show, to perform tricks, to make us ooh and ahh for a spectacular overhead lift and laugh with an unexpected yet intentional collision. Although they perform some synchronized movement, Wells’ laid-back choreography never enforces conformity. Some dancers shine more than others, but that is more an indicator of accumulated experience than of a lack of necessary talent. A fab flurry of athletic dancing closes the evening. Darcy runs up a wall and flips head over heels. Others run sideways to the wall and propel themselves into dive rolls onto a well-placed mat. Growden is a superb jumper with a loft to rival any high jumper. When he dives horizontally at the brick wall, two other men arrive to pin him, freezing the moment in time. Wells plays often with this kind of sustained time, floating bodies, pausing handstands, and full-body catches that linger, not so much frozen as floating, and then when released the falling weight becomes the momentum that drives the dance onward.

(A few months later I deleted a little joke of a line at the end that seemed to color the previous writing too much. There are comments by two of the men in the cast and another local choreographer - going further with questions of queer, masculinity, dance.)

Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, Small Dances About Big Ideas

Modern dance, beginning with Isadora Duncan’s bare legs, uncorseted breasts and critical rants about women, socialist Russia, dancing children and free bodies, has always been political. Acknowledging the influence of formalism, minimalism, and various styles of abstraction, contemporary dance continues to engage social issues or pose socially resonant questions. But a dance about genocide and international law? Would it be doomed to disappoint or just depress? Despite Liz Lerman’s national reputation, I wasn’t surprised that they were giving tickets away in last minute email blasts to the local dance community. Who wants to see a dance about targeted mass murder? How can a dance meaningfully address horrors of this scale? With four free tickets, I could only convince one friend to accompany me...

Photo by Enoch Chan

Liz Lerman Dance Exchange

Small Dances About Big Ideas

Kanbar Hall, Jewish Community Center

San Francisco 4/19/2009

Modern dance, beginning with Isadora Duncan’s bare legs, uncorseted breasts and critical rants about women, socialist Russia, dancing children and free bodies, has always been political. Acknowledging the influence of formalism, minimalism, and various styles of abstraction, contemporary dance continues to engage social issues or pose socially resonant questions. But a dance about genocide and international law? Would it be doomed to disappoint or just depress? Despite Liz Lerman’s national reputation, I wasn’t surprised that they were giving tickets away in last minute email blasts to the local dance community. Who wants to see a dance about targeted mass murder? How can a dance meaningfully address horrors of this scale? With four free tickets, I could only convince one friend to accompany me. As I approached the theater I found myself repeating a new motto received from a UC Davis colleague Sampada Aranke, “Failure is generative.” Looking at failed utopian action as ripe with potential shifts the witness/critic role and encourages a more nuanced engagement with a performance or action.

Early in the piece, Lerman sits in a chair, her lap filled with notes, a mic in her hand, and begins to tell a story of being invited to make a dance for a conference at Harvard commemorating the 60th anniversary of the Nuremberg trials. She shared how she expressed doubt in the project, and how she was moved to request personal support and guidance to do the work. Charmed by this meta-performance that welcomed doubt and anticipated failure, I relaxed into my chair.

I have followed Lerman’s career as a choreographer, teacher, and thinker for over 20 years. Her projects inspire and facilitate social dialogue about ethically contentious issues, including refugees, genetic research, and now genocide. The dance company, Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, is diverse with respect to race/ethnicity and age. Lerman says that younger dancers dance better in the presence of older people, and she attributes this to love, the love that older people offer freely to youth. In

Small Dances

I was more often drawn to the two dancers that I perceived as the eldest, Thomas Dwyer, a tall lean white haired man and Martha Wittman, a long-haired woman who seemed to be the spiritual mother of the piece. Lerman is known in classrooms and studios around the world for Liz Lerman’s Critical Response, a methodology, which guides artists and teachers to give critical feedback without assuming culturally specific standards. The artist-centered process is based more in questioning than judging; it challenges the ideas of a common standard of artistic quality or aesthetic sense and supports cross-cultural collaboration. This multi-decade dedication to the art of social justice makes Lerman a likely candidate from whom to request a dance about the failure of international law to prevent genocide.

Small Dances About Big Ideas

premiered in November, 2005, at "Pursuing Human Dignity: The Legacies of Nuremberg for International Law, Human Rights and Education.”

In her opening monologue Lerman advocates a role for the body in political and historical discourse, especially in response to the often paralyzing impact of information and opinion. So what do the bodies do in this dance? Dramatic expression. Mimetic gesture. Representational images. The dancers line-up and get shot with staccato staggering and dense falls to the ground. They run in fear. Matt Mahaney represents Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide and successfully advocated for a special class of international laws. The dynamic Mahaney/Lemkin jumps and waves, trying to get attention for his cause. When he fails, he falls repeatedly, almost violently. Stylistically the dancing and gestures recall socialist-inspired expressionist dance from the 30s, or the 70s ground-breaking feminist collective The Wallflower Order (which became SF’s Dance Brigade.) Ted Johnson, who plays the judge, could have done the same postures in Kurt Joos’ famed anti-war dance

The Green Table

(1932). Small Dances is postmodern in form but not in gesture, except when they fall, and here they release into the floor, spiraling to soften the impact. A younger man, Benjamin Wegman, shares the narrator role with Lerman. He introduces the characters represented by the dancers. There are the three mythical

Norns

(Shula Strassfeld, Meghan Bowden, and Wittman), Norse deities older than god, akin to Fates, who inhabited the waters in and under Nuremberg. Their natural hair, tattered scarves, long dresses, and a concern for the others, attempted to conjure a mythical feminine presence. There is Lemkin and the stoic, shiny bald, black robed Judge. Cassie Meador played The Bone Woman, based on forensic anthropologist Clea Koff who investigated atrocities in Rwanda. And there were two other characters that I called the man from Rwanda (Fiifi Abadoo) and the Bosnian woman (Sarah Levitt). I wanted more contact with these dancers, wanted to know which language they were actually speaking (as opposed to the languages I assumed for them), wanted to know even a hint of their personal story. How do they function, or identify themselves within the American-ness of Lerman’s perspective? Were they born here or there or where? The narrator played a reporter, a watcher. He seemed to speak both for Lerman and for us. What does genocide look like from across the gap of geography or generation? What does the witness do with the harrowing information and the implication of responsibility? The question was put before us, within us, and this alone validated the performance.

Lerman and her dancers wandered through the material like devastated archeologists, stepping over bodies, pausing to investigate the bones which hold all the memory of violence, daring to record the details of machete and sex. They touched bodies as if listening to their past. “Rape cannot be claimed as self-defense, ” someone claims. We have to think about that. Now. Lerman’s choreographic process led us on a difficult descent. She told us of being haunted by stories and bodies, but unable to stop the research. There’s too much to read. She lost the ability to remember in the evening a simple fact that she was told in the morning. And then she can’t sleep.

The most successful moment in the work led to its paradoxical disappointment. With all eyes looking forward to the proscenium stage, we were jolted by a loud sound at the back of the house. We turned to see the source of disruption, the narrator. He shook the protective aisle rail like it was a cage. Something fell and broke. It seemed dangerous, like maybe he had snapped, and had pushed the ‘play’ too far. The room was still, tense, charged. He told us that he was done listening, that he didn’t want to hear anymore. He questioned what was happening, and therefore he questioned our role, like his, of watching. He said, it’s good to talk about genocide, even to just try out the word, and that maybe we should just talk amongst ourselves. He was walking towards the stage as he spoke and we could now see that the other performers were watching him. No one was dancing. The stage was quiet. Lerman sat in the shadows, attentive. The house lights were up and we started to talk. I was with Neil MacLean, a researcher who has spent years on the questions posed by this project. I spoke about my resistance to the dancing and representational movement. I told him that the gesture of one arm chopping the other arm was done by David Byrne in the early 80s

Stop Making Sense

tour and I’ve thought it weird and undecipherable in too many choreographies since then. Neil sharped the focus and told me why he and many others find the term genocide problematic. He said that it should be ethnocide or something to indicate that it is not people (genus) but a specific family of people (ethnicity) that is under attack. We discussed how the politics of identity, including politics of naming and resisting genocide, often subvert potential solidarity by intensifying cultural and ethnic difference. And then our attention was guided back to the stage, and we were led in a group dance of mimetic gestures about pulling a story from the space around us, holding it, and then passing it to the person beside us. Although 90% of the audience participated in this follow-the-leader dance, I found it difficult to participate whole heartedly. It seemed to suggest a common experience and way of processing the intensity of the material, but really it served to pull us out of the intensity and back to dancing, as if synchronized dancing is a unifying experience, when Lerman and I both know that stories, bodies, and gestures are loaded with positions and identities that are more exclusive than inclusive.

The work continued for another 15 minutes or so, but I was still stuck in the break, in the disruption, in the moment of questioning what we were doing in a theater with this handsome group of sincere and talented people, and what good might come from speaking the word genocide aloud, together. Two weeks later, I’m still bothered, still asking.

I heard that after the performance, a World War II vet asked Lerman,“Is this adequate?” She acknowledged that it wasn’t. Of course the work failed to save lives already gone or rewrite UN charters or prosecute countries, including the US, who regularly shit on international law. I gathered with friends in the lobby. We were the minority who didn’t stay for the post-show discussion with Lerman & company. The lobby chat was lively and sharp. Although we had perspectives that resonated, no two of us had the same opinions about the work, about what happened, about what didn’t, what should have or might have. Respect for the work was our most shared experience. We were inspired to challenge or defend art’s role in addressing state violence. We felt pressed to reconsider historic atrocities and to strategize ways to prevent and recover from the kind of totalizing violence which permanently scars time, space, and community. This small dance, only 60 minutes long, idiosyncratic and maybe even trite, invited us to interact with history, with how violence, rape, and massacre are remembered and historicized. Lerman and company not only dared to accept this ethical imperative, but they held our hand and invited us to dance along, among the bones, which continue to haunt and to speak. Honoring a lineage of politically engaged choreographies, Liz Lerman’s

Small Dances About Big Ideas

touches people and helps us to listen.

Featured Posts

-

Essays

- Dec 31, 2005 ONLY IN SAN FRANCISCO? Homegrown trends and traditions (2005) Dec 31, 2005

- Dec 31, 2005 KEITH HENNESSY'S TOP 10 LOCAL DANCE EVENTS OF 2005 Dec 31, 2005

- Oct 31, 2008 Tracing the Roots of Contact Improvisation in the Bay Area 1972-1982 Oct 31, 2008

- Dec 21, 2008 ANOTHER QUEER, CRITICAL OF THE EXPENSIVE AND MISGUIDED FIGHT FOR GAY MARRIAGE Dec 21, 2008

- Dec 21, 2008 DELINQUENT MUSINGS, a little about me Dec 21, 2008

- Jun 1, 2009 Joah Lowe, my first SF dance teacher Jun 1, 2009

- Sep 16, 2009 WHY I READ MY TEXTS IN PERFORMANCE Sep 16, 2009

- Sep 20, 2010 The Mission School (of Painting) Sep 20, 2010

- May 13, 2013 848: queer, sex, performance in 1990s San Francisco (article DRAFT) May 13, 2013

- May 23, 2014 Notes on the T-word Debates of 2014 May 23, 2014

- Aug 22, 2014 Cop killings in the SF Bay Area, a small list Aug 22, 2014

-

Reviews

- Jul 3, 2008 Castorf at Berlin's Volksbuhne, July 3 2008 Jul 3, 2008

- Jul 7, 2008 Friederike Plafki & Maria Francesca Scaroni in Berlin Jul 7, 2008

- Sep 3, 2008 Trannyshack Finale Sep 3, 2008

- Jan 11, 2009 DRACUL: PRINCE OF FIRE, A BALLET! Jan 11, 2009

- Jan 13, 2009 DRACUL: PRINCE OF FIRE, A BALLET! (short review) Jan 13, 2009

- Apr 19, 2009 Penny Arcade BITCH! DYKE! FAGHAG! WHORE! Apr 19, 2009

- Apr 19, 2009 Pichet Klunchun & Myself (Jerome Bêl) Apr 19, 2009

- May 18, 2009 Lizz Roman & Dancers AT PLAY May 18, 2009

- May 19, 2009 Big Art Group's S.O.S. at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts May 19, 2009

- May 20, 2009 Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, Small Dances About Big Ideas May 20, 2009

- Jun 4, 2009 Scott Wells & Dancers, Men Want To Dance Jun 4, 2009

- Oct 11, 2009 Passing Strange (The Musical / Film) Oct 11, 2009

- Mar 31, 2010 Kirk Read performance at Too Much! (Jan 2010) Mar 31, 2010

- Jul 7, 2010 Jess Curtis / Gravity • Dances for Non/Fictional Bodies Jul 7, 2010

- Sep 20, 2010 Bay Area Dance - 2008 - The West Wave Dance Festival Sep 20, 2010

- Dec 29, 2010 Tiara Sensation - avant-drag pageant Dec 29, 2010

- Jan 19, 2011 Dance.Eats.Money. - Ishmael Houston-Jones on The A.W.A.R.D. Show Jan 19, 2011

- Jan 26, 2011 Top 10 Youtubes, Jan 2011 Jan 26, 2011

- Feb 12, 2011 Deadly Disappointing Eonnagatta Feb 12, 2011

- Oct 10, 2014 This Is The Girl / Funsch Dance Experience, Sep 2014 Oct 10, 2014

- Oct 23, 2014 Hope Mohr Dance / Have we come a long way, baby? Oct 23, 2014

-

Texts

- Dec 31, 2005 The War Prayer by Mark Twain Dec 31, 2005

- Dec 31, 2005 Mark Twain Preface (2005) Dec 31, 2005

- Dec 31, 2005 Illegal Bride (2005) Dec 31, 2005

- Sep 5, 2009 PERFORM THE KEITH SCORE Sep 5, 2009

- Mar 28, 2013 10th Anniversary of the War Against Iraq (Illegal Bride) Mar 28, 2013

- Apr 1, 2013 10th Anniversary of the War & Occupation of Iraq (I Tried To Stop The War) Apr 1, 2013

- Apr 2, 2014 I wanna daughter so I can kill cops Apr 2, 2014

Archive by year

-

2019

- Aug 15, 2019 Taking to the Soil: A Reprise and Response to Spring Circle X

- Aug 15, 2019 QUEERED CARE to hear INDIGENOUS VOICES SPEAK

- Mar 20, 2019 Encounters through, around, and within Winter Circle X

- Mar 20, 2019 Unsettling Cycle (Winter Circle X)

-

2014

- Oct 23, 2014 Hope Mohr Dance / Have we come a long way, baby?

- Oct 10, 2014 This Is The Girl / Funsch Dance Experience, Sep 2014

- Aug 22, 2014 Cop killings in the SF Bay Area, a small list

- May 23, 2014 Notes on the T-word Debates of 2014

- Apr 16, 2014 Watch your mouth!

- Apr 4, 2014 Paid Jobs I've Had

- Apr 2, 2014 I wanna daughter so I can kill cops

-

2013

- Aug 28, 2013 The Lady Gaga Method Practiced by Marina Abramović

- May 13, 2013 848: queer, sex, performance in 1990s San Francisco (article DRAFT)

- Apr 1, 2013 10th Anniversary of the War & Occupation of Iraq (I Tried To Stop The War)

- Mar 28, 2013 10th Anniversary of the War Against Iraq (Illegal Bride)

-

2011

- Apr 26, 2011 Mau: Lemi Ponifasio responds to Peter Sellars